Knowledge and Training Lecture

1.0 INTRODUCTION

“But what if I make a mistake?' Will asked.

Gilan threw back his head and laughed. 'A mistake? One mistake? You should be so lucky. You'll make dozens! I made four or five on my first day alone! Of course you'll make mistakes. Just don't make any of them twice. If you do mess things up, don't try to hide it. Don't try to rationalise it. Recognise it and admit it and learn from it. We never stop learning, none of us.”

John Flanagan, Erak’s Ransom (2010)

“An organisation’s ability to learn, and translate that learning into action rapidly, is the ultimate competitive advantage.”

Jack Welch (in Slater, 1999)

Most businesses that demonstrate an ability to maintain an enduring competitive advantage appear to recognise the importance of gaining, retaining and deploying knowledge effectively. To do so over time requires an ability to learn so that the corporate knowledge and ‘know-how’ can be effectively harnessed (Hamel, 2005). It follows that knowledge and learning form the foundation for the intellectual assets of any company and that these capabilities are vested within the competence base of the people involved (Beardwell & Thompson, 2014).

This Chapter will seek to explore the concept of knowledge and knowledge management within a business context, using core academic models to provide an appropriate framework. This is then developed into a discussion of the issues surrounding organisational learning and the corporate challenges that emerge for any business seeking to maintain their competitive positioning. Whilst key tools and techniques (such as performance and development agreements) should be used to embed learning and harness knowledge in order to support corporate strategy, these are explored in greater depth within Chapter 3.8.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

To be able to:

- Understand the concept and nature of knowledge.

- Appreciate how to share and exploit both tacit and explicit knowledge.

- Discuss the various approaches to the understanding of organisational learning.

- Understand and explain the concept of systems thinking.

2.0 KNOWLEDGE

Information is essentially raw data placed in some form of context. This context gives that information meaning and utility, which is essential if the basic facts that comprise that information are to be understood and appreciated by the people concerned. When this is further shaped by judgement - where people either collectively or individually apply their skills and experience - then a position of knowledge has been reached (Chaffey and Wood, 2005).

The complexity associated with capturing exactly what knowledge is clearly demonstrated in the opening paragraph - if it is affected by context and individual/collective understanding then it can be argued that it is a fairly fluid concept! It can be situated, abstract, implicit, explicit, distributed and individual, physical and mental, static and developing, verbal and encoded (Blackler, 1995). Whilst many of these concepts are explored later in this Chapter, perhaps a more formal categorization of recognised ‘knowledge types’ may be of more use:

- Embedded knowledge - such as that captured in corporate technologies, rules and organisational procedures.

- Encultured knowledge - the collective understanding, values and beliefs shared by those working in an organisation, supported by ‘stories’ (i.e. ‘this is the way we do things around here’).

- Embodied knowledge - the more practical, activity-based knowledge often captured by a business in the form of defined competences and skills requirements. Essentially ‘know-how’.

- Embraced knowledge - recognising and deploying the conceptual understanding or cognitive abilities of key group members (i.e. ‘the subject matter expert’).

(Armstrong & Taylor, 2014)

However, even this explanation does not clearly capture the essence of knowledge which for most businesses emerges from the collective experience of work and how that is subsequently shared between members of a group or even across groups (such as a corporate supply chain) (Scarborough & Carter, 2000). Exploring how knowledge can be ‘built’ in a little more detail may provide further clarity:

- Data consists of the basic (usually agreed) facts such as sales and purchasing figures.

- Once that data has been processed to generate meaning and purpose for people it becomes information e.g.developing the raw sales and purchasing data to give indication of consumer trends.

- When that information is put to productive use for a company it can then be regarded as knowledge - adding the skills and competences and understanding (embodied and embraced knowledge) that shapes business decision making. For example, changing material purchasing plans to reflect anticipated/emerging changes in consumer demand.

(Henry, 2011)

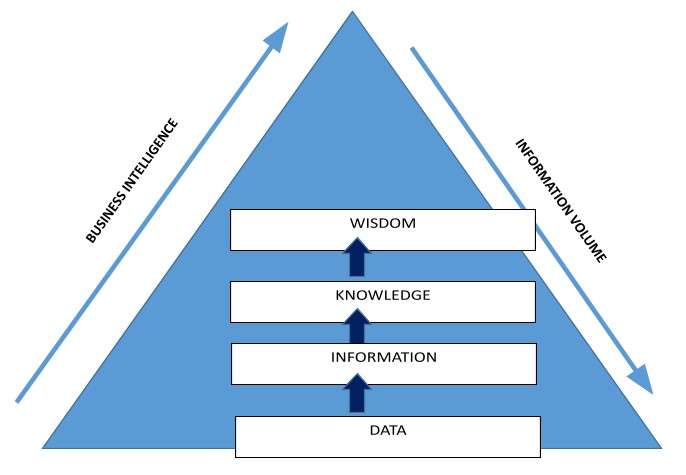

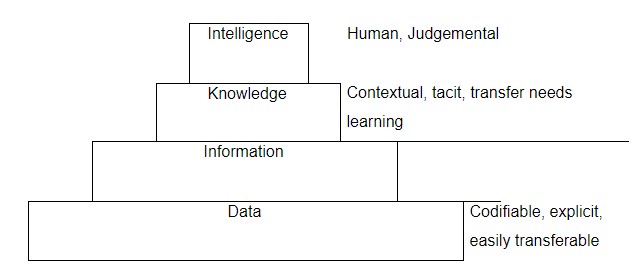

Diagrams 1 and 2 provide illustrations of these concepts:

Adapted from Newell, Robertson, Scarborough & Swan, 2009)

Diagram 1: The Knowledge Hierarchy

|

Intelligence |

Human, Judgemental |

|||||||

|

Knowledge |

Contextual, tacit, transfer needs learning |

|||||||

|

Information |

||||||||

|

Data |

Codifiable, explicit, easily transferable |

|||||||

(Adapted fromSkyrme, 1999)

Diagram 2: The Components of Corporate Knowledge

Discussion Point:

Having reviewed the issues presented so far (and the concepts captured in Diagrams 1 and 2), how would you define knowledge?

Think about planning a presentation evening for your work colleagues. What would form the basis of the data required and what would happen to turn that data into knowledge that helps you organise the event? What ‘intelligence’ or ‘wisdom’ would you be likely to apply?

2.1 TACIT AND EXPLICIT KNOWLEDGE

Given these arguments, then a company that wishes to develop and sustain a competitive advantage needs to be able to capture and deploy different types of knowledge effectively. This requires the ability to understand the inter-relationship that exists between tacit and explicit knowledge i.e.:

- Explicit knowledge is that which is consciously held by individuals and groups and as such it should be relatively easy to share. An example could be the sales figures highlighted above - these can be clearly communicated and quantified through a range of formats such as printed reports, graphs to illustrate trends and staff presentations to highlight key aspects.

- Tacit knowledge is more internalised and individual in nature and those possessing it may not be consciously aware of how the possess and deploy this knowledge. This brings it into the category of ‘intelligence’ or ‘wisdom’ highlighted in Diagrams 1 and 2 (above). An example could include the seasoned/experienced sales manager urging her superiors not to act on a particular set of figures as she had ‘seen such trends before and they are likely to change substantially in the next quarter’.

(Nonaka, 1994)

Need Help With Your Business Assignment?

If you need assistance with writing a business assignment, our professional assignment writing service can provide valuable assistance.

See how our Assignment Writing Service can help today!

It is therefore argued that the main challenge for any business is how to turn critical tacit knowledge into a form that can be more easily shared across the company. To do so effectively requires a clear knowledge management strategy that recognise how human interaction rather than formal constructs (such as shared databases) provides the best way of moving tacit knowledge across an organisation.

Many consulting organisations rely on their ability to capture and deploy the tacit knowledge held by their clients and internally within the company. For example, Arthur Andersen (a professional services firm) used editors and journalists to interview their consultants to create a ‘best practice’ knowledge base. These people possessed the interviewing skills and interpersonal abilities to effectively capture corporate ‘know-how’ that had previously been held by only a few ‘indispensable’ consultants. This approach allowed these subject-matter experts to share knowledge that they had previously found hard to contextualise in a way that had meaning for others (Bukowitz & Williams, 1999: 189).

Discussion Point:

What tacit knowledge do you possess? Are you able to share this effectively with your colleagues? If so, how? If not what makes it difficult for you to pass this knowledge on to others?

2.2 EPISTEMOLOGY

For those who wish to explore the concept of knowledge in greater depth than the potentially simplistic split between tacit and explicit forms, then it is possible to review the numerous philosophical texts on epistemology - the essential theory of knowledge. Whilst these texts can sometimes prove extremely challenging, for any business it is useful to explore some of the core concepts such as:

- How knowledge and perceptions of facts can be shaped and altered by people’s beliefs and attitudes.

- The challenges associated with ‘cognitive dissonance’ in business, where staff will only seek out or only accept information that reinforces their existing attitudes and beliefs.

- The importance of intuition in business - where a decision may be taken because it ‘feels’ right.

(Landesman, 1997)

Further reading is recommended at 4.1 (below), which some may find worth exploring given the current political and media debate around ‘true facts’!

2.3 KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

Knowledge Management:

“The promotion and formalisation of learning within the workplace with the aim of aligning training with the needs of the business”.

(Mullins & Christy, 2016: 620)

“Processes and practices through which organisations generate value from knowledge”.

(Henry, 2011: 434)

Knowledge management within a business is usually focussed on practices and procedures that identify, create, distribute and share knowledge, with an understandable modern fixation within IT applications such as corporate intranets, data warehousing and decision support systems (such as automated stock ordering) (Armstrong & Taylor, 2014). These codification strategies are essentially people-to-information approaches, whereby knowledge is taken from the person or group that developed it, made independent in some form (such as an email, handbook, noticeboard or an electronic library) and then access to it by others is provided.

However, the challenges of sharing tacit knowledge have already been highlighted. The best corporate knowledge management approaches therefore also support personalisation - building the person-to-person networks and face-to-face interactions essential for the development of knowledge as a corporate asset (Mullins & Christy, 2016). Conferences, workshops, brainstorming opportunities and informal gatherings are essential if a business is to develop knowledge rather than manage information.

2.3.1 FACTORS SHAPING THE SHARING OF KNOWLEDGE

Whilst the basic/core knowledge sharing approaches have been discussed above (see 2.3), it is important to understand how the effectiveness of such mechanisms can be shaped by factors such as organisational culture, power structures, leadership and management. These aspects are explored in greater depth in Chapters 3.6 and 1.3. It may also prove useful to review the discussion around ‘learning lessons’ in Project Management (Chapter 1.9).

Discussion Point:

How does your company manage and share knowledge? Is it effective? What could/should be done differently?

Does your company really share knowledge or just distribute information? What is the difference?

3.0 LEARNING

Learning:

“A change of a relatively permanent kind that may result in new behaviours and actions or new understanding and knowledge gained through a formal process or spontaneously and incidentally through life experiences”.

(Mullins & Christy, 2016: 620)

Learning is about increasing the capability and capacity to take action through the acquisition and application of new knowledge. Many business entities can often confuse learning with training which may explain some of the corporate challenges surrounding knowledge management! Training is only one of several approaches which can be used to promote learning (Armstrong & Taylor, 2014). This is a fundamental point when considering this area - learning can only be stated to have taken place when those involved are able to take more effective action as a result, demonstrating the ability to detect and correct related errors (Argyris, 1993). Knowledge transfer is not learning - improved knowledge application is!

3.1 LEARNING STYLES

As intimated earlier in this Chapter, individuals will have differing approaches and attitudes to learning. If knowledge transfer and subsequent application is to be effective, this requires an appreciation of your learning style - the way in which you perceive, conceptualise, organise and recall information (Huczynski & Buchanan, 2013).

The ‘VARK’ model developed by Fleming (2011), suggests four distinct preferences or approaches and these are outlined in Diagram 3:

|

VISUAL A preference for the use of images and graphics to process information (e.g. maps and flow charts). |

AUDITORY Learn through listening and speaking, so likely to prefer lectures and group discussions. Often able to retain information through repetition and the use of mnemonics e.g. VARK! |

|

READING/WRITING Learn best through words. Often able to translate sometimes abstract concepts into clear written statements. A preference for note-taking and reading ‘around’ the learning topic |

KINESTHETIC Prefer a more tactile, ‘hands-on’ approach to learning. Actively seek opportunities to take part in more physical activities in order to develop their skills (i.e. ‘having a go’!) |

(Fleming, 2011)

Diagram 3: Learning Preferences

Whilst this outlines how we may prefer to learn, it is sensible to consider other models that help to further develop an appreciation of how business development interventions need to consider and reflect different learning styles.

3.2 LEARNING THEORY

Numerous learning theories exist, each of which generally apply a different emphasis on key aspects of the learning process.

3.2.1 BEHAVIORIST PERSPECTIVE

As suggested by the title, behaviourists are focussed on the clearly observable and identified changes in behaviour following learning interventions. The basic concepts are rooted in the animal research work of Pavlov, Skinner and Watson who suggested that learning is the formation of new connections between stimulus and response on the basis of experience, which they called conditioning (Clegg, Kornberger & Pitsis, 2011). The theory argues that we modify our responses to key inputs (stimuli) depending on how previous feedback when faced with a similar situation was presented (i.e. ‘good’ or ‘bad’). In the workplace this translates into the application of positive reinforcement through incentives to encourage repeat behaviour and/or negative reinforcement (through deterrent and sanctions) to prevent similar behaviour (Beardwell & Thompson, 2014).

Businesses relying on scripted, standardised approaches often apply such methodologies such as fast food outlets and call centres. However, many argue that this is overly simplistic and manipulative and that such approaches do not encourage broader knowledge sharing or initiative (e.g. staff may have the ability to improve established working routines) (Torrington, Hall, Taylor & Atkinson, 2011).

3.2.2 COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE

Compared to the behaviourist approach, cognitive theorist are more interested in what goes on in the heads of learners! The focus is on understanding how people think and how that shapes what they understand and know. Rather than considering how to institutionalise behaviour, attention is given to motivation and how learners are likely to derive meaning from their experiences. There is a broader emphasis on development (learning to learn) and it is recognised that people have the capability to absorb information, principles and facts and then decide how they choose to apply that learning (Armstrong & Taylor, 2014).

Formal course and structured training interventions (such as development programmes) tend to underpin this approach, with clear performance feedback mechanisms to provide appropriate motivation (e.g. rewards for key skills/competency development). A very rational approach is taken to learning, but of course learners are not always rational! To be truly effective, any development interventions need to consider the learning style(s) of the staff concerned (see 3.2 below) (Torrington et al, 2011).

3.2.3 CONSTRUCTIVIST APPROACH

This approach considers how the personality of an individual and their past experiences shape attitudes to learning. This means that every member of staff has the potential to view or understand a learning intervention in a different way depending on the unconscious ‘meaning’ they have given when faced with similar situations (Torrington et al, 2011). For example, someone may have experienced a poor tutor when on a computer training course and attributed their subsequent failure as being due to their perceived inability to work with computers. Consequently, they may actively resist future computer training interventions (considering them a wasted effort) based on that experience.

Constructivists therefore seek to create learning ‘experiences’ that aim to address such barriers whilst also stimulating involvement that encourages people to share knowledge and skills whilst building learning groups - often through the involvement of ‘facilitators’ (Armstrong & Taylor, 2014). If you have ever had to face a corporate outward bound or adventurous training ‘event’ (or even just 360° feedback approaches) then you have been at the mercy of a Constructivist!

3.2.4 SOCIAL LEARNING THEORY

Social learning theory focuses on the development that can occur within a social context and how people can learn from one another through observation, imitation and modelling. For those businesses seeking to capture and deploy tacit knowledge (see 2.1 above), this approach is seen as being of fundamental importance (Newell et al, 2009). Seeking to capture this dynamic through the creation of communities of practice (see 3.5.3 below) helps to challenge existing constraints such as organisational culture and power dynamics which can undermine social learning by reinforcing the ‘wrong’ lessons. These aspects are explored in greater depth in Chapter 3.6.

This ‘observational learning’ is often carried out in a business through the appointment of mentors and role models as well as the creation of peer support groups. The challenge is to allow staff the opportunity to challenge the learning they are being given in order to avoid embedding undesirable or institutionalised behaviours (Bandura, 1977). For example, a shared dress code may be good, but this could unintentionally lead to discrimination against some social/cultural groups.

Discussion Point:

Consider the training and development interventions you have experienced in your workplace. Which learning theory appeared to underpin the approach taken? What events proved to be most effective for you (and/or your team) and why?

3.2.5 KOLB’S LEARNING CYCLE

Kolb developed a cyclical model of learning outlining how learning was a process that created knowledge through the transformation of experience (Kolb, Rubin & McIntyre, 1974). This involved four key stages:

- Concrete experience or DO - where learners actively takes part in a workplace activity such as laboratory experimentation or production line processes.

- Reflective observation (OBSERVE) - the learner consciously reflects on this workplace activity, considering its effectiveness and significance.

- Abstract conceptualisation (THINK) - developing a range of concepts and ideas that the learner can consider applying when facing a similar situation.

- Active experimentation (PLAN) - working out how to test these concepts and ideas in new situations. This leads to the next concrete experience (DO) and the cycle of learning continues.

(Armstrong & Taylor, 2014)

Kolb argues that to learn effectively, staff need to be encouraged to move between being direct participants and observers to allow for an element of analytical detachment and that those responsible for training need to understand how individual learning styles shape each experience (Mullins & Christy, 2016). As a part of this model, Kolb also considered learning preferences which a business will need to understand:

- Accommodators - those who are prepared to learn by ‘trial and error’, often combining the ‘plan’ and ‘do’ elements of the learning cycle.

- Divergers - those keen to reflect and with the ability to consider a work situation from a number of different points of view.

- Convergers - those comfortable with practical experimentation and translating theory into action.

- Assimilators - those keen to create their own theoretical models!

(Armstrong & Taylor, 2014)

Need Help With Your Business Assignment?

If you need assistance with writing a business assignment, our professional assignment writing service can provide valuable assistance.

See how our Assignment Writing Service can help today!

3.2.6 HONEY AND MUMFORD’S APPROACH

Honey and Mumford developed Kolb’s thinking around learning preferences, noting how individuals displayed clear preferences for each element of the learning cycle that had been created (Honey & Mumford, 1996). The four patterns of behaviour they developed (which are not exclusive - people can display a mix of these aspects depending on the situation and their character/personality traits) are:

- Activists - those keen to take on new challenges. Whilst living in the ‘here and now’, such individuals can quickly become bored with routine and may not always consider longer term consequences.

- Reflectors - prefer to think about new situations, stepping back to observe and collect data and then developing a broader perspective. Can sometimes be considered over-cautious.

- Theorists - taking a logical and disciplined approach, developing a rationale and objective view. Can sometimes be seen as perfectionists.

- Pragmatists - keen to try out new ideas to see if they work in practice. Often considered as practical problem-solvers, such individuals can lose focus when involved in long-term discussions.

(Mullins & Christy, 2016)

In creating project teams, a successful (or pragmatic!) business should seek to include individuals with a mix of learning styles in order to create an appropriate balance that maintains the required corporate focus. A team built exclusively from Theorists may think everything through, but end up delivering nothing! Alternatively, a group of Activists could end up creating unsustainable business models.

Discussion Point:

What learning styles and preferences do you believe you have and how do you adapt to make sure that you gain the most from any development interventions?

Further Reading Research:

Complete a Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) assessment to examine how your personality ‘type’ is reflected in your learning preferences. Also consider the use of ‘Johari’s Window’ to challenge your thinking and perceptions.

3.3 ACTION LEARNING

In order to create the balance alluded to, as well as considering individual learning styles a business seeking to develop effective learning and knowledge management structures can build ‘action learning sets’. These involve a small, engaged group of learners who meet regularly to consider the challenges presented by real work situations. An example may include workers on the same production line involved in different (but linked) processes (Clegg et al, 2011). Action learning seeks to use group dynamics and reflective practice to find viable solutions to problems through review and experimentation (reflection in action) and a consideration of how activities have shaped outcomes, particularly when things have gone wrong (reflection on action) (Linstead, Fulop & Lilley, 2009).

Action learning approaches aim to create a shared knowledge base by bringing together a pool of relevant subject matter experts to solve specific problems. They form the foundation of cross-functional, multi-disciplinary teams which can prove more effective at developing broader learning and building a corporate knowledge base as they are less constrained by organisational structures and hierarchies (Beardwell & Thompson, 2014). Importantly, this helps to build the trusted relationships which sit at the heart of social learning theory (see 3.2.4 above). This issues are explored further in the discussion around organisational learning (3.5).

3.4 THE LEARNING CURVE

No Chapter on learning would be complete without at least an outline consideration of the importance of the learning curve. In essence, this refers to the time it takes an inexperienced person to reach the required level of performance in a job (Armstrong & Taylor, 2014). It is important to recognise that learning may not necessarily be a steady, incremental process as employees will require time to reflect, absorb and master what they have already learnt before moving on to the next aspect of the role or task. This requires the transfer of learning (where the new information or skills can be effectively applied to the task or role and not just in a training scenario or learning context) and the time required to do so shapes the learning curve (Business Essentials, 2013). Diagram 4 provides an illustration of this concept:

(Adapted from Armstrong & Taylor, 2014)

Diagram 4: The Learning Curve

One example of the measured use of learning curve principles relates to the British Army’s approach to the physical development of new recruits. Traditionally, a standard (blue line) approach was taken, but this resulted in a high injury rate with. Taking a more stepped approach (red line), allowed more recruits to finish training to the same exacting physical standards. However, this required a significant organisational and cultural change given the lower physical standards required earlier in the training process and perceptions that the army was being ‘too soft’ on new recruits.

3.5 ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING

Organisational Learning:

“The process by which a company can build a collective or shared knowledge base and the development of mechanisms to retrieve and disseminate this knowledge”.

(Hora & Hunter, 2014)

We have already considered how a business derives value and competitive positioning from knowledge and that people are the intellectual assets of the organisation. As a consequence, it is vital for any business to consider how to develop and retain that organisational expertise, whilst also involving staff in the process (French, Rayner, Rees & Rumbles, 2008).

Two contrasting learning philosophies often exist - a predominantly instructional approach focussed on remedial action to correct errors or omissions (the approach favoured by fast-food outlets and call centres); and a more comprehensive lifelong learning point of view that is adopted by entities that appreciate how employee development is essential if competitive positioning is to be maintained within a knowledge-based economy (Beardwell & Thompson, 2014). The former approach considers what needs to be done to ensure that staff possess the skills and attitudes needed to perform their current role effectively. Lifelong learning views staff as assets (rather than elements of production), capable of taking on more onerous responsibilities that can help a company face future competitive challenges (Malone, 2003).

3.5.1 ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING CONCEPTS

The core assumption is that as a company grows and adapts to its operating environment it generates a store of institutional knowledge that, if harnessed effectively, can deliver a business benefit that exceeds that provided by employees operating individually. Collective learning generates organisational knowledge by combining formal systems with the shared experiences of employees - the explicit/tacit mix discussed earlier in this Chapter (Johnson, Whittington, Scholes, Angwin & Regnér, 2014).

To do so, requires a company that can create a culture comfortable with challenge and review (see Chapter 1.4) if it is to be able to change its way of doing business in response to the application of this expanded knowledge base. The more traditional, rigid business hierarchies built around command and control do not necessarily create the best conditions for organisational learning. There needs to be a recognition that knowledge and know-how is possessed by the ‘collective’ (i.e. all staff) and not just managers and leaders (Cohen & Sproull, 1996).

So what is the foundation for this knowledge and learning base? A business requires its employees to possess/develop skill in the person (developed through education, training and experience), skill in the job (meeting functional competency/role requirements) and skill in the setting (being able to relate personal knowledge to both collective/corporate interests and company culture) (Johnson et al, 2014). Organisational learning approaches seek to maximise the collective return from this mix by creating the right working environment and culture. Ultimately, the aim is to create a business position that any competitor would find difficult to imitate (Hatch & Cunliffe, 2006).

3.5.2 APPROACHES TO ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING

It is argued that effective organisational learning required the application of five key disciplines:

- Personal mastery - linking individual aspirations to company goals (often through mechanisms such as performance and development agreements).

- Mental models - encouraging staff to consider future business needs by creating a culture of reflection and enquiry.

- Shared vision - creating a collective/common purpose with individual and team targets clearly linked to that purpose.

- Team learning - building group development interactions with training focussed on meeting shared goals.

- Systems thinking - using staff knowledge and feedback to develop an overview of key interdependencies so that corporate systems can be refined and simplified.

(Senge, 1990)

Discussion Point:

What is your corporate mission and vision? (Also consider business values and (top level) goals). How are you involved in shaping and meeting these corporate aspirations?

The intent is to use mission and vision statements (underpinned by shared objectives) to create a collective framework which shapes corporate learning interventions - in essence ‘what are we all trying to achieve together’? In order to sustain this collective commitment and employee engagement, it is often necessary to carry out frequent learning/development interventions in order to build an enduring capability for change and innovation (Huczynski & Buchanan, 2013). The aim is to maximise the return by combining ‘know-why’ (essentially best practice), ‘know-who’ (which staff possess the expertise and skills to deliver best practice) and ‘know-how’ (creating a learning environment that shares ‘know-why’ and ‘know-who’ to encourage wider corporate innovation).

3.5.3 COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE

Efforts to capture the critical aspect of “know-how” has led to the creation of cross-functional Communities of Practice as an organisational approach to learning (Lave & Wenger, 1998). Such groups seek to use the informal, more social interaction of groups to create engagement rather than rely on more structured knowledge transfer approaches. These groups often demonstrate the ability to capture essential tacit knowledge (a particular weakness of more formal mechanisms) as staff feel more involved in the decision-making process. This more personal interaction creates engaged participation, as a sense of collective ownership can develop - again, what are we going to do to resolve this shared problem? (Esterby-Smith, Burgoyne & Araujo, 1999). (Relate this concept to some of your more formal training interventions such as time in a lecture theatre or listening to a team briefing - were you really engaged?)

In creating a shared concern (or even passion!) about a problem or business topic, the group become comfortable with regular interaction and are proactive in sharing/distributing their expertise and knowledge. Many businesses now create teams that work across organisational boundaries to drive corporate innovation and solve emerging problems (Wenger, McDermott & Snyder, 2002). However, caution is advised here - creating the opportunities that bring people together does not necessarily build a Community of Practice! Too much structure, control and management of a Community of Practice can re-introduce and reinforce the corporate constraints that these informal peer groups should work around/against (Eraut, 2002).

3.5.4 ISSUES AROUND ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING

When looking to develop any organisational approach to learning, it is important to guard against some challenging issues that can emerge:

- Superstitious learning. It is too easy for a company to learn the ‘wrong’ things if the links between actions and outcomes are not clearly specified. Staff can build incorrect assumptions between cause and effect i.e. because I did this, a certain outcome was delivered. This may not be the case and (if so), poor working practices can be reinforced.

- Ambiguity of success. Where the measures of corporate success are constantly changed, it is difficult to measure what has actually been learned. A key objective may have been met, but what was learned as a result? Did performance really improve?

- Competency Traps. Improving procedures or practices that do not deliver any real competitive advantage or operating efficiency create an illusion of organisational progress. In reality, they expose the company to competitors able to focus on improvements that deliver practical business benefits that meet customer requirements. Perhaps this could better be described as ‘moving the deckchairs on the Titanic’!

(Hatch & Cunliffe, 2006)

Need Help With Your Business Assignment?

If you need assistance with writing a business assignment, our professional assignment writing service can provide valuable assistance.

See how our Assignment Writing Service can help today!

4.0 SUMMARY

Effective knowledge management and good learning practices go hand-in-hand. If a company wishes to maintain an enduring competitive advantage in a modern economy built around technology and innovation then they will need to work harder at gaining access to the tacit knowledge held by their staff. This Chapter has been able to discuss the core principles with a particular focus on organisational learning, but these need to be adapted to reflect the specific needs of each company and the business sector or segment they compete in.

Whatever approaches are adopted, it is vital that the challenges associated with corporate culture (and potentially change management) are considered. These aspects are discussed in other Chapters, but unless learning and development interventions address cultural aspects (and the informal power relationships that result) then they are likely to fail. It would also be prudent to consider a broader perspective when seeking to harness corporate knowledge through the involvement of business stakeholders. For example, sharing best practice across the supply chain could help to address performance issues that shape corporate social responsibility targets (see Chapter 1.5).

This Chapter has deliberately not considered learning delivery mechanisms in any depth. Issues such as e-learning, on-the-job training, mentoring and coaching are obviously important but they must be tailored to reflect the issues that have been outlined here. Efforts to capture and deploy corporate knowledge through innovative development mechanisms will fail unless the learning needs and styles of individuals are effectively matched to the demands of the business. Whilst the creation of a unifying mission and vision and linked organisational and personal objectives can create the right environment, this is just the start. A company must be prepared to create supported opportunities for staff to successfully challenge established business practices if organisational learning is to take place.

Critically consider the training and development approaches of your organisation and how (if) they are linked to organisational objectives.

Do you work in a learning organisation? If so, what mechanisms (and company culture) exist to support you in capturing and sharing tacit knowledge? If not, what could be done to improve the situation?

What about your company’s competitors? Are they better or worse than your business at knowledge management and what can you learn from them?

4.1 RECOMMENDED TEXTS

Armstrong, M., Taylor, S. (2014). Armstrong’s Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice, 13th Edition, London: Kogan Page Ltd.

Mullins, L.J., Christy, G. (2016). Management & Organisational Behaviour, 11th Edition, Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

5.0 REFERENCES

Argyris, C. (1993). Knowledge for Action: A guide to overcoming barriers to organisational change, San Francisco: Jossey Bass Inc.

Armstrong, M., Taylor, S. (2014). Armstrong’s Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice, 13th Edition, London: Kogan Page Ltd.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Beardwell, J., Thompson, A. (2014). Human Resource Management: A Contemporary Approach, 7th Edition, Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Blackler, F. (1995). Knowledge, Knowledge Work and Experience, Organisation Studies, 16(6), pp. 16-36.

Bukowitz, W.R., Williams, R.L. (1999). The Knowledge Management Fieldbook, Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Business Essentials. (2013). Human Resource Development and Employee Relations, 3rd Edition, London: BPP Learning Media.

Chaffey, D., Wood, S. (2005). Business Information Management: Improving Performance Using Information Systems, Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Clegg, S., Kornberger, M., Pitsis, M. (2011). Managing & Organisations: An Introduction To Theory & Practice, 3rd Edition, London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Cohen, M.D., Sproull, L.S. (1996). Organisational Learning, London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Easterby-Smith, M., Burgoyne, J., Araujo, L. (Eds) (1999). Organisational Learning and the Learning Organisation: Developments in theory and practice, London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Eraut, M. (2002). Conceptual analysis and research questions: do the concepts of 'learning community' and 'community of practice' provide added value? [Online], Available: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED466030.pdf [09 March, 2017].

Flanagan, J. (2010). Erak’s Ransom: Ranger’s Apprentice, Toronto: Philomel Books.

Fleming, N.D. (2011). Teaching and Learning Styles; VARK Strategies, 2nd Edition (revised), Christchurch NZ: N D Fleming.

French, R., Rayner, C., Rees, G., Rumbles, S. (2008). Organisational Behaviour, 9th Edition, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Hamel, G. (2005). MT Master Class. Management Today, July 2005, p.5.

Hatch, M.J., Cunliffe, A.L. (2006). Organisation Theory: modern, symbolic, and postmodern perspectives, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Henry, A.E. (2011). Understanding Strategic Management, 2nd Edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hora, M.T., Hunter, A. (2014). Exploring the dynamics of organisational learning: identifying the decision chains science and math faculty use to plan and teach undergraduate courses. International Journal of STEM education, 2014(1), p.8.

Huczynski, A., Buchanan, D.A. (2013). Organisational Behaviour, 8th Edition, Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Johnson, G., Whittington, R., Scholes, K., Angwin, D., Regnér. P. (2014). Exploring Strategy: Text and Cases, 10th Edition, Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Kolb, D.A., Rubin, I.M., McIntyre, J.M. (1974). Organisational Psychology: An experimental approach, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc.

Landesman, C. (1997). An Introduction to Epistemology, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers Inc.

Linstead, S., Fulop, L., Lilley, S. (2009). Management & Organisation: A Critical Text, 2nd Edition, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Malone, S.A. (2005). Learning About Learning: An A to Z of Training and Development Tools and Techniques, London: CIPD.

Mullins, L.J., Christy, G. (2016). Management & Organisational Behaviour, 11th Edition, Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Newell, S., Robertson, M., Scarborough, H., Swan, J. (2009). Managing Knowledge Work and Innovation, 2nd Edition, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nonaka, I. (1994). A Dynamic theory of organisational knowledge creation. Organisational Science, 5(1), p19.

Scarborough, H., Carter, C. (2000). Investigating Knowledge Management, London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

Senge, P. (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organisation, New York: Doubleday Currency.

Skyrme, D.J. (1999). Knowledge Networking: Creating the Collaborative Enterprise, Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd.

Slater, R. (1999). Jack Welch and the GE Way: Management Insights and Leadership Secrets of the Legendary CEO. New York: McGraw-Hill

Torrington, D., Hall, L., Taylor, S., Atkinson, C. (2011). Human Resource Management, 8th Edition, Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Wenger, E., McDermott, R., Snyder, W.M. (2002). Cultivating Communities of Practice: A guide to managing knowledge, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

6.0 BIBLIOGRAPHY

Burton-Jones, A. (1999). Knowledge Capitalism: business work and learning in the new economy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Davenport, E., Hall, H. (2002). Organisational knowledge and communities of practice. Annual review of Information Science and Technology, 36, pp.171-227.

Knights, D., Willmott, H. (Eds) (2012). Introducing Organisational Behaviour and Management, 2nd Edition, Andover: Cengage Learning EMEA.

Sanchez, R. (2003). Knowledge Management and Organisational Competence, 2nd Edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cite This Module

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: