Macbeth Quotes: A Comprehensive Academic Guide

Info: 5047 words (20 pages) Study Guides

Published: 24 Mar 2025

Part of: Macbeth

The tragedy Macbeth by William Shakespeare features powerful quotations that encapsulate the play’s deepest themes and moral questions. For both undergraduate and postgraduate students, understanding these key quotes in context is crucial for analysing the play’s exploration of ambition, kingship, the supernatural, and gender roles. Each significant line in Macbeth carries philosophical weight and drives the narrative forward. This reflects the characters’ inner conflicts and the play’s broader Jacobean context. This guide presents a well-structured list of essential Macbeth quotes, with detailed analysis and academic insight into their meaning and significance.

By examining these quotations – from Macbeth’s soliloquies to Lady Macbeth’s chilling appeals and the prophetic riddles of the Witches – we illuminate how Shakespeare’s language conveys the play’s complex interplay of themes. (All quotes appear with [Act.Scene] references. Harvard-style citations refer to scholarly analyses, with a full reference list provided.)

Ambition and the Tragic Flaw in Macbeth

Shakespeare presents ambition as Macbeth’s hamartia (tragic flaw), driving his rise and downfall. From the outset, Macbeth struggles between moral restraint and his “black and deep desires”(1.4). After learning he might be king, he muses: “If chance will have me king, why, chance may crown me, / Without my stir” (1.3) – indicating a brief willingness to leave his fate to fortune rather than assassinate King Duncan.

However, as soon as Duncan names Malcolm as heir, Macbeth’s aside “Stars, hide your fires; Let not light see my black and deep desires” (1.4) reveals his growing intent to conceal his ambition in darkness. The imagery of light and dark here symbolises morality – Macbeth knows his desire to be king is wrong. As a result, he must hide it. This line foreshadows his willingness to betray honorable values under the cover of night.

“I have no spur / To prick the sides of my intent, but only / Vaulting ambition, which o’erleaps itself / And falls on th’other” (1.7).

Analysis: In his soliloquy before killing Duncan, Macbeth admits that nothing motivates him to commit regicide except his “vaulting ambition.” He compares ambition to a wild horseman over-jumping a hurdle and crashing – a metaphor suggesting that excessive ambition propels one beyond reason and leads to ruin. This self-awareness shows that Macbeth understands the moral peril: his ambition might cause his own downfall.

As scholar Susan Snyder notes, Macbeth concludes that Duncan has given him no just cause for murder – “I have no spur” – highlighting that Macbeth acts from pure ambition rather than any legitimate grievance. Thus, Shakespeare portrays Macbeth’s unchecked ambition as a destructive force; it is the tragic flaw that subverts his noble qualities and ultimately “o’erleaps” his moral restraints, precipitating his collapse (Snyder 2013).

This aligns with the classical idea that the hero’s overreaching ambition brings about his tragic end.

“To be thus is nothing; / But to be safely thus” (3.1)

Analysis: Now crowned King, Macbeth reflects that mere kingship means nothing unless he can secure his position. This anxious aside reveals how ambition, once satisfied, breeds only more paranoia and violence. Macbeth fears Banquo and the witches’ prophecy that Banquo’s lineage will rule; he feels insecure on his “fruitless crown.” His words illustrate a key idea: illicit power gained by evil means yields no true contentment.

As one study observes, Macbeth’s ambition has “no other motivation.” Thus, once he attains the throne, his lack of an heir and guilty conscience make his reign hollow. The quote underlines that Macbeth’s ambition: instead of bringing him peace or glory, it leaves him with a “restless ecstasy” of fear and the necessity to commit further crimes (Smith 2020). Shakespeare thereby condemns unrestrained ambition: it only leads Macbeth into a spiral of insecurity, moral decay, and eventual destruction.

Kingship and Tyranny: “Macbeth Kingship Quotes” in Context

The theme of kingship is central to Macbeth. It contrasts the virtuous, divinely-sanctioned rule of Duncan (and later Malcolm) with Macbeth’s tyrannical usurpation. In Shakespeare’s time, citizens regard the king as God’s appointed ruler – the doctrine of the “Divine Right of Kings.” Accordingly, regicide is a crime against the natural and spiritual order (Bhebhe 2023). Macbeth reflects this belief. King Duncan exemplifies the ideal monarch: just, humble, and benevolent.

Macbeth himself acknowledges Duncan’s kingly virtues and the wickedness of destroying such a righteous ruler. To wit: “This Duncan hath borne his faculties so meek, hath been / So clear in his great office, that his virtues / Will plead like angels trumpet-tongued against / The deep damnation of his taking-off” (1.7). In this vivid simile, Shakespeare presents Duncan’s “virtues” (goodness, justice) as angels proclaiming the sin of murdering him. Macbeth recognizes that killing a legitimate, kindly king will invoke eternal damnation. As Snyder observes, Shakespeare deliberately portrays Duncan as an innocent, almost saintly king. Ergo, that Macbeth “cannot justify his actions by the perceived misdeeds of his victim” (Snyder 2013) folger.edu. The play thus emphasizes that Duncan’s murder is a heinous violation of the moral and political order.

Each new morn…

Once Macbeth seizes the throne, Scotland falls under the rule of a tyrant. Shakespeare uses the country’s deterioration and other characters’ language to underscore the difference between lawful kingship and destructive tyranny.

Under Macbeth, “Each new morn … new sorrows / Strike heaven on the face” (4.3). Scotland is described as a suffering motherland: “our country … weeps, it bleeds” under Macbeth’s oppression (4.3). Malcolm later lists the “king-becoming graces” – “justice, verity, temperance, stableness, / Bounty, perseverance, mercy, lowliness, / Devotion, patience, courage, fortitude” (4.3). All are virtues that define a true king, all lacking in Macbeth’s reign.

By contrast, Macbeth’s rule is one of bloodshed, fear and cosmic disorder. A critical study notes that “Macbeth’s illegal and immoral kingship brings death, destruction, and suffering to Scotland, whilst the good kingship of Duncan and Malcolm brings victory and prosperity.” (Abdul Muttaleb & Rawashdeh 2019).

“Tis unnatural, even like the deed that’s done. On Tuesday last / A falcon, towering in her pride of place, was by a mousing owl hawked at and killed” (2.4).

The chaos engulfing Scotland after Duncan’s murder symbolically reflects this. This report of an owl (a night creature) killing a falcon (a royal bird) is a blatant inversion of the natural order, mirroring Macbeth’s unnatural act of regicide. The image would not have been lost on Shakespeare’s audience – it signifies that Macbeth’s tyranny has inverted the ordained hierarchy of nature (Royal Shakespeare Company 2020).

Shakespeare repeatedly labels Macbeth a “tyrant” to reinforce his illegitimacy. Loyal Scottish nobles refer to him as “this tyrant, whose sole name blisters our tongues” (4.3). Calling him “the tyrant” rather than “the king” implies he holds the crown but is unworthy of it. Macbeth’s inability to fill the role of a true king comes through in the metaphor “now does he feel his title / Hang loose about him, like a giant’s robe / Upon a dwarfish thief” (5.2). He is but a small man who stole the throne. He is also unworthy of the “giant’s robe” of kingship that doesn’t fit him.

In the end, Macbeth’s tyranny collapses and Malcolm – the rightful heir – takes his rightful place. This re-establishes moral and political order. Malcolm’s closing judgement calls Macbeth and Lady Macbeth “this dead butcher and his fiend-like queen” (5.9). It emphasies that under Macbeth’s rule, the nobility’s expectations of a king is now nothing but savage butchery. The contrast between Duncan’s benevolent kingship and Macbeth’s bloody usurpation thus highlights Shakespeare’s lesson.

In essence, legitimate rule we base on justice and order is “a direct blessing from God.” Whereas a tyrant’s rise through ambition and murder brings only chaos until he is overthrown (Bhebhe 2023)

The Supernatural and Moral Disorder: “Macbeth Supernatural Quotes”

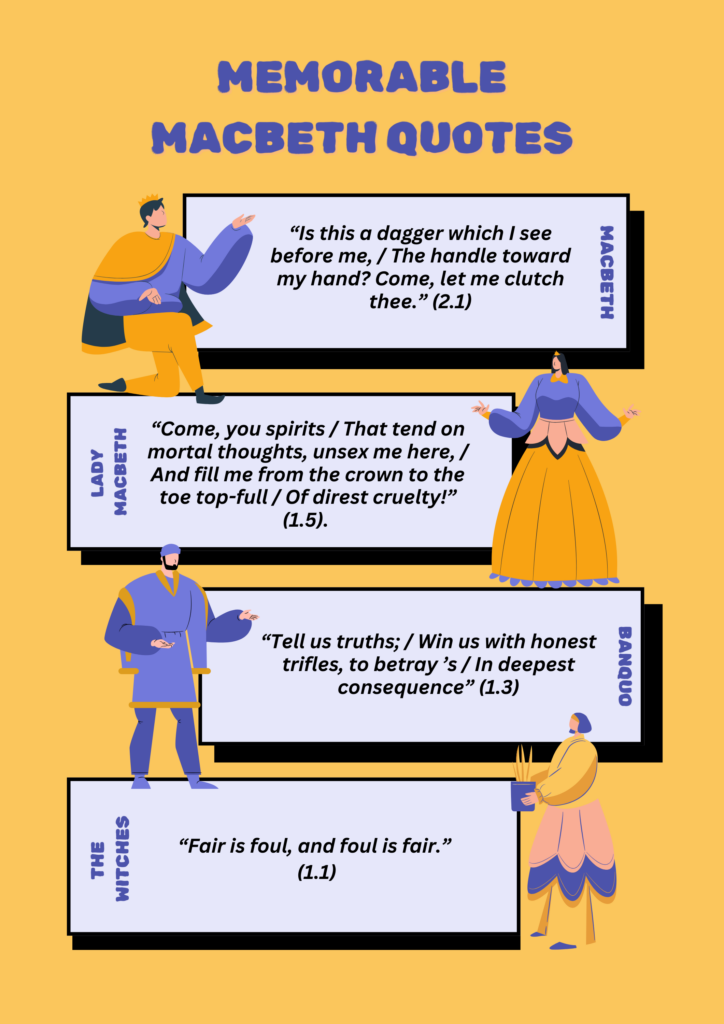

From the opening scene, Macbeth employs supernatural elements that blur the line between reality and the occult. The play famously begins with the Witches’ chant, “Fair is foul, and foul is fair” (1.1). This is a paradox that establishes an atmosphere of moral ambiguity and equivocation. This phrase implies that in Macbeth’s world, appearances deceive. That is, what seems good (“fair”) can be evil (“foul”) and vice versa. Critics note that this maxim introduces a “moral ambivalence” that pervades the play.

Indeed, as the plot unfolds, characters and events are seldom what they seem. The supernatural utterance “fair is foul…” sets the stage for a tragedy where the natural moral order is inverted (Zitner 1964). It also reflects the play’s eerie tone: the “fog and filthy air” through which the Witches “hover.” This suggests a world where clarity is lost and evil forces roam.

Tell us truths; / Win us with honest trifles, to betray ’s / In deepest consequence” (1.3)

The Weird Sisters (or Witches) are the most obvious supernatural agents, delivering ambiguous prophecies that spur Macbeth’s actions. When Macbeth and Banquo first encounter them, Banquo is immediately wary. He cautions that such dark beings may “tell us truths; / Win us with honest trifles, to betray ’s / In deepest consequence” (1.3). In other words, evil forces (the “instruments of darkness”) might lure people to harm by telling small truths that lead to big betrayals. Banquo’s insight proves correct: the witches predict Macbeth’s rise accurately, but they withhold the dangerous consequences. As Professor Alexander Leggatt explains, Banquo’s warning means that the witches’ prophecies are deliberately equivocal: they “win [Macbeth] to his harm” by inflating his confidence with truths, only to betray him later.

This sets up one of the play’s central questions: are the witches independent supernatural evils who tempt Macbeth, or do they merely reveal Macbeth’s own inner ambitions? The drama leaves their exact nature ambiguous (Leggatt 2016), but their influence is undeniable. Notably, they are called “weird sisters” (from wyrd, fate), suggesting they represent destiny or prophetic fate. Yet, Shakespeare also shows Macbeth exercising free will in interpreting and acting on their words, meaning the moral responsibility still lies with him.

“Is this a dagger which I see before me?” (2.1)

Beyond the witches, Macbeth features other supernatural or hallucinatory phenomena that reflect the psychological turmoil of the characters. On his way to murder Duncan, Macbeth has a famous vision: “Is this a dagger which I see before me, / The handle toward my hand? Come, let me clutch thee. / … Or art thou but / A dagger of the mind, a false creation, / Proceeding from the heat-oppressed brain?” (2.1).

This ghostly dagger leading him to Duncan’s chamber symbolizes Macbeth’s guilty conscience and the pull of evil on his mind. He cannot tell if it’s real or a “false creation” of his stress and ambition. The hallucination illustrates how the supernatural in the play often merges with psychological reality. Macbeth’s imagination, inflamed by his “heat-oppressed” (fevered) brain, projects an image that emboldens him to proceed with the murder.

The dagger also foreshadows the bloody path Macbeth is about to take. One analysis states Macbeth’s inability to distinguish reality from hallucination “suggests his guilt has already taken hold” before committing the crime. Similarly, after the murder, he hears an ethereal voice cry “Sleep no more! Macbeth does murder sleep” (2.2). This indicates his crime against nature (killing a king in his sleep) invokes a kind of supernatural curse. Namely, he shall never know innocent sleep again due to his overwhelming guilt.

“Never shake thy gory locks at me!” (3.4)

Supernatural manifestations continue to haunt Macbeth, the most dramatic being Banquo’s ghost at the banquet (3.4). When Macbeth sees the spectre of his slain friend, invisible to others, he is terrified and cries out, “Never shake thy gory locks at me!” (3.4). The ghost’s bloody hair nodding at Macbeth is a projection of Macbeth’s guilt and paranoia, come to torment him. Lady Macbeth dismisses it as merely a figment of his fear – “This is the very painting of your fear… / Why do you make such faces? When all’s done, / You look but on a stool” (3.4) – but to Macbeth the apparition is intensely real.

Whether Banquo’s ghost is truly a supernatural event or a psychological breakdown, Shakespeare uses it to show that Macbeth has become deeply entangled with unnatural forces. By this point, Macbeth himself is identified by the witches as “something wicked” that comes when they sense his approach (4.1). In other words, he has crossed into the realm of the supernatural through his heinous actions. Thus, he’s effectively becoming part of the evil. This fulfilment of the witches’ opening paradox – the once “noble” Macbeth is now wicked – demonstrates how thoroughly the moral order has been upended.

“Come, you spirits / That tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here, / And fill me from the crown to the toe top-full / Of direst cruelty!” (1.5)

Interestingly, Lady Macbeth initially welcomes the supernatural, whereas Macbeth is largely a victim of it. In Act 1, Scene 5, upon hearing of the prophecy, Lady Macbeth calls on dark spirits.

“Come, you spirits / That tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here, / And fill me from the crown to the toe top-full / Of direst cruelty!” (1.5).

Unlike Macbeth who is startled by the witches’ greetings, Lady Macbeth embraces the supernatural to aid her purpose. She implores demonic forces to strip away her feminine compassion and replace it with remorseless cruelty. As scholar A. Leggatt notes, “the power that terrifies Macbeth is a power that Lady Macbeth deliberately calls on.”

Her invocation is an unmistakable sign of unnatural desire. Accordingly, she seeks to transcend her human (and gendered) nature to commit evil. This moment links the supernatural theme with the theme of gender, which we will explore next. Crucially, even Lady Macbeth cannot ultimately withstand the consequences of inviting dark powers.

By the play’s end, Lady Macbeth is driven mad by guilt. She’s obsessively trying to wash an invisible bloodstain from her hands in her sleepwalking scene. She makes the famous cry, “Out, damned spot! … who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him?” (5.1). This shows that the supernatural guilt (the “damned” spot of blood) has permeated her mind irreversibly. Thus, through hallucinations, ghosts, and witches, Shakespeare uses the supernatural to:

- externalise inner conflicts and;

- to signal the collapse of natural order under Macbeth’s regicide.

The result is a play where reality itself seems poisoned by evil – truly a “foggy” world where foul is fair. (Marler 2013)

Gender Roles and Power: Lady Macbeth and Lady Macduff

One of the most intriguing aspects of Macbeth is its examination of gender roles and expectations. The play repeatedly questions what it means to be a man or a woman in a patriarchal, violent society. Two female characters in particular – Lady Macbeth and Lady Macduff – serve as foils in exploring female agency, motherhood, and the inversion of traditional gender norms. Throughout the play, courage, aggression, and brutality are coded as masculine traits, while compassion and gentleness are coded as feminine.

Shakespeare, however, complicates these stereotypes.

- Lady Macbeth famously rejects the submissive, nurturing role assigned to her gender, whereas;

- Lady Macduff embodies the era’s ideal of womanhood (loving and maternal), condemning her husband for not protecting his family.

By analysing “Lady Macbeth quotes and analysis” alongside “Lady Macduff quotes,” we gain insight into how Macbeth interrogates the intersection of gender and power.

Lady Macbeth: Challenging and “Unsexing” Gender Norms

From her first appearance, Lady Macbeth subverts expectations of feminine behavior. Upon reading Macbeth’s letter about the witches’ prophecy, she fears her husband is “too full o’ the milk of human kindness” to take the crown (1.5). Determined to propel Macbeth to the throne, she summons dark forces to strip away her femininity.

“Come, you spirits / That tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here, / And fill me… top-full of direst cruelty! / Make thick my blood; / Stop up th’ access and passage to remorse” (1.5).

In this soliloquy, Lady Macbeth begs to be “unsexed.” This implies that the qualities associated with women – compassion, empathy, maternal care – hinder her from committing cold-blooded murder. She asks her blood to be made thick (i.e. to feel no pity). She also requests that her ability to feel remorse to be cut off. As Sara Laux explains, Lady Macbeth believes she must reject her womanly nature (or “weaknesses”) to pursue her ambition and make Macbeth king.

The language of this quote is violent and supernatural, aligning Lady Macbeth with demonic forces and masculine cruelty. By calling on murderous “spirits,” she becomes an agent of the supernatural. She shows how the theme of gender ties into the theme of evil in the play. Lady Macbeth’s desire to be “unsexed” is Shakespeare’s commentary on the constrictive gender norms of his time. In fact, she can only exercise power by figuratively transforming herself into a man (or a sexless, inhuman being). Notably, this speech would have originally been delivered by a male actor (since women were banned from the Elizabethan stage). And so it adds a further layer of gender-bending performativity to the moment.

“When you durst do it, then you were a man” (1.7)

Lady Macbeth’s manipulation of gender expectations continues as she engineers Duncan’s murder. She repeatedly questions Macbeth’s manhood to goad him into action. When Macbeth wavers, saying “We will proceed no further in this business” (1.7), Lady Macbeth scornfully asks: “Art thou afeard / To be the same in thine own act and valour, / As thou art in desire?” and “When you durst do it, then you were a man” (1.7).

Here, she equates manhood with the courage to pursue ambition at all costs. To her, being a “man” means being bold, resolute, and unfettered by conscience or compassion. By accusing Macbeth of being “afeard” (cowardly) and essentially saying he was more of a man when he dared to imagine killing Duncan, Lady Macbeth attacks his masculinity as a means of control. This tactic is devastatingly effective. As H. Regan observes, Lady Macbeth “unsettles conventional norms of gender by questioning his masculinity,” narrowing Macbeth’s idea of manhood to ruthless action.

“I dare do all that may become a man; Who dares do more is none” (1.7)

Macbeth feels compelled to prove himself. He famously asserts, “I dare do all that may become a man; Who dares do more is none” (1.7), meaning “I dare do anything proper for a man; whoever does more (such as the immoral act of regicide) is not a man at all.” Ironically, under his wife’s relentless challenge, Macbeth abandons this initial moral stance.

Lady Macbeth even claims she herself would have killed her own infant while nursing if she had sworn to do so, graphically declaring “I would, while [the baby] was smiling in my face, / Have plucked my nipple from his boneless gums / And dashed the brains out, had I so sworn as you / Have done to this” (1.7).

This shocking image of a mother capable of infanticide illustrates Lady Macbeth’s total repudiation of the gentle, life-giving roles of wife and mother. She uses it to shame Macbeth’s hesitation as unmanly. In effect, Lady Macbeth adopts a masculine posture of violence and resolve more extreme than her husband’s, showing how she transgresses gender roles to achieve power.

Innocent Flower and The Serpent

Another key instruction from Lady Macbeth encapsulates the theme of deceptive appearances (tied to gender and power). She advises Macbeth to “Look like th’ innocent flower, but be the serpent under ’t” (1.5) when Duncan visits. Superficially, this means Macbeth should hide his murderous intent behind a façade of friendly hospitality. The serpent under the flower is a biblical allusion to Satan’s deception in Eden and, as historians note, likely a reference to a medal of a serpent among flowers that King James I had commissioned after the Gunpowder Plot attempt on his life.

Every Jacobean spectator would grasp the symbolism of treachery lurking beneath innocence. Thus, Lady Macbeth is coaching her husband in duplicitous behavior, a trait considered dishonourable and unmanly in the chivalric code. Yet she deems it necessary to achieve their ambitions.

This quote highlights how Lady Macbeth uses any means – even instructing Macbeth to feign the opposite of his true intent – to secure power. Her dominance in this scene also inverts typical gender dynamics: she is the strategist, the cool mastermind, while Macbeth is shaky and needs bolstering. In fact, contemporary critics often view Lady Macbeth as an embodiment of the dangerous, “unnatural” woman who disrupts the patriarchal order.

“Here’s the smell of the blood still. All the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little hand” (5.1)

Shakespeare shows the consequences of such disruption through Lady Macbeth’s fate. After Duncan’s murder, her strength begins to unravel. The sanguinary acts she set in motion haunt her into madness. In the sleepwalking scene, Lady Macbeth is observed obsessively washing her hands and lamenting, “Here’s the smell of the blood still. All the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little hand” (5.1). This line poignantly contrasts with her earlier claim that “a little water clears us of this deed” (2.2).

Initially she had scoffed that they could simply wash away the evidence of murder and with it, the guilt. Now, tormented by conscience, she imagines an indelible blood smell and believes nothing can cleanse her. Lady Macbeth’s arc—from a woman invoking dark powers and denying her sex, to a broken figure damned by guilt—illustrates the psychological cost of defying one’s natural feelings. Ultimately, she cannot wholly “unsex” herself; her suppressed humanity resurfaces in the form of crushing remorse. Her suicide off-stage in Act 5 is the final outcome of her inner disintegration.

Through Lady Macbeth, Shakespeare presents a complex exploration of gender and power: she gains influence by embracing ruthless “masculine” traits and spurning “feminine” compassion, but in doing so she destabilizes her mind and unleashes forces (both psychological and supernatural) that destroy her. Lady Macbeth’s famous quotes thus track a trajectory from chilling strength to pathetic fragility – offering a cautionary example of the perils of contravening the accepted gender roles of the time and the moral law.

Lady Macduff: Motherhood, Innocence and the Cost of War

In stark contrast to Lady Macbeth, Lady Macduff represents the Elizabethan ideal of womanhood – domestic, loving, and innocent – and her role, though brief, powerfully underscores the human cost of Macbeth’s tyranny. Abandoned by her husband Macduff who flees to England, Lady Macduff appears in Act 4, Scene 2 as a mother protecting her children and lamenting her husband’s absence. Through her, Shakespeare explores the expectation that a man’s duty is to defend his family, and a woman’s is to care for the household.

The Natural Touch & The Poor Wren

Lady Macduff feels Macduff has failed in his role as husband and father. “He loves us not; / He wants the natural touch” (4.2) she says, meaning Macduff lacks the “natural touch” of affection and responsibility toward his family. She even tells her young son that his father is “dead” to them due to his apparent desertion.

In a poignant metaphor, Lady Macduff remarks, “the poor wren, / The most diminutive of birds, will fight, / Her young ones in her nest, against the owl” (4.2). This imagery contrasts a tiny mother bird heroically defending her chicks against a predator with Macduff’s flight to England. Lady Macduff implies that even the smallest of creatures will stand their ground to protect their offspring, so her husband’s decision to leave his family undefended is unnatural and cowardly in her eyes. Susan Snyder explains that to Lady Macduff, Macduff’s flight “seems to signify fear rather than natural love.”

In this scene, the play explicitly mourns the breakdown of the “natural” order of family due to political chaos. Lady Macduff embodies the innocent victims of Macbeth’s violence; she is utterly blameless and removed from the male ambition that drives the plot, yet she and her son pay the ultimate price.

Tragically, Lady Macduff’s righteousness cannot save her. When Macbeth’s hired murderers arrive, she is bewildered: “Wherefore should I fly? / I have done no harm” (4.2). Her disbelief at being targeted – she has “done no harm” – highlights the senseless cruelty of Macbeth’s rule. The audience witnesses the horrifying slaughter of Lady Macduff and her child on stage, sharpening the play’s emotional impact. This moment reinforces the theme of tyranny’s toll on innocent life, and it also serves as a foil to Lady Macbeth’s earlier invocation of infanticide. Lady Macduff dies trying to protect her son, illustrating true motherly love – the very quality Lady Macbeth renounced. Through Lady Macduff’s quotes and fate, Shakespeare evokes pathos and moral outrage, strengthening the audience’s desire for Macbeth’s downfall.

Lady Macduff and Masculinity challenges

Lady Macduff’s story also prompts a crucial conversation about masculinity between Malcolm and Macduff in Act 4, Scene 3, after Macduff learns of his family’s murder. Stricken with grief, Macduff cries “All my pretty ones?… at one fell swoop?” (4.3), comparing the murder of his children to a hawk (Macbeth) swooping down on defenseless chicks.

“I shall do so; / But I must also feel it as a man” (4.3)

Malcolm urges him to “Dispute it like a man” – to take revenge – but Macduff replies with a line that redefines manhood in the play: “I shall do so; / But I must also feel it as a man” (4.3). In saying this, Macduff asserts that feeling sorrow and compassion is not contrary to being a man. He insists on grieving for his wife and children and then channeling that grief into vengeance. This is a direct counterpoint to Lady Macbeth’s earlier view that emotions are “unmanly.” As the Shakespeare Navigators commentary notes, Malcolm’s idea of manhood at first is the familiar “real men don’t cry,” but Macduff “knows better” – genuine manhood can encompass both emotional sensitivity and righteous anger.

“I could play the woman with mine eyes / And braggart with my tongue” (4.3)

Macduff even says, “I could play the woman with mine eyes / And braggart with my tongue” (4.3), meaning he could weep like a woman and boast like a man simultaneously, but he chooses sincere feeling over performative shows.

This exchange is critical: it presents an evolved ideal of masculinity, one that values honour and empathy rather than brute aggression alone. When Macduff later faces Macbeth, he carries both his sorrow and his resolve for justice. He ultimately fulfills both aspects of manhood – avenging his family (he kills Macbeth in single combat) and openly mourning them. In doing so, Macduff restores a sense of moral order and humane values to Scotland.

Through Lady Macduff and Macduff, Macbeth thus examines gender roles on multiple levels. Lady Macduff’s quotes highlight the expected “natural” bonds of family and the chaos when those bonds are broken. Macduff’s response to loss then broadens the definition of manliness to include emotional integrity. Meanwhile, Lady Macbeth’s trajectory showed the destructive consequences of rejecting traditionally “feminine” qualities like compassion altogether. In the end, Macbeth suggests that a balance of qualities – courage tempered with conscience, ambition checked by compassion – is necessary for a healthy society.

The play’s exploration of gender is ahead of its time in some respects: it recognizes the folly of equating brutality with strength (a lesson hard-earned by Macbeth) and suggests through Macduff that true strength can include heartfelt emotion. Lady Macbeth’s and Lady Macduff’s experiences, though very different, both underscore that the disruption of natural gender roles (whether by a woman adopting violence or a man neglecting care) yields tragic outcomes. Shakespeare, especially through Lady Macduff and Lady Macbeth quotes, offers a nuance-driven commentary on gender and power. Macbeth quotes convey this memorably through its characters’ dialogue.

Conclusion About Macbeth Quotes

The quotes examined above are among the most significant in Macbeth, each illuminating critical facets of the tragedy’s meaning. From Macbeth’s soliloquies about ambition and moral conflict, to the supernatural utterances of the witches, to the charged exchanges on kingship and gender, Shakespeare’s language is rich with philosophical and thematic significance. These lines do more than advance the plot – they invite readers to ponder timeless questions about the nature of evil, the corrupting influence of power, the rightful qualities of a leader, and the dynamics of gender and morality.

Importantly, the context and analysis of each quote reveals how interconnected the play’s themes are. For instance:

- Macbeth’s ambition rises thanks to prophecy (fate vs free will);

- his descent into tyranny upsets the natural order, and;

- his actions provoke responses that challenge the era’s gender norms.

By providing academic analysis supported by scholarly sources, this guide has sought to go beyond surface interpretation and demonstrate the depth in Shakespeare’s work.

Macbeth remains a cornerstone of English literature study precisely because its key quotes carry layers of meaning – political, ethical, and psychological – that reward close reading and critical discussion. For students and scholars, engaging with these quotations in context is essential for a full appreciation of how Macbeth dramatizes the darkest consequences of human ambition and desire. In the final measure, the play’s enduring power lies in how its language captures the “sound and fury” of a mind and a society unraveling, offering a cautionary tale that still resonates in contemporary discourse on leadership and morality.

References (Harvard style)

- Abdul Muttaleb, F. & Rawashdeh, M. (2019). Macbeth’s Political Imagination: The Struggle for Kingship in Macbeth – Jerash for Research and Studies, 20(1). (Quote on good vs. immoral kingship)digitalcommons.aaru.edu.jo

- Bhebhe, M. (2023). How Is Kingship Presented In Macbeth? (analysis of divine right and kingship). Read With Us.

- Folger Shakespeare Library (2013). Macbeth: A Modern Perspective – Essay by Susan Snyder. (Analysis of Macbeth’s motives, Duncan’s virtue)

- Leggatt, A. (2016). The Instruments of Darkness – Stratford Festival Insights. (Scholarly commentary on witches and supernatural elements in Macbeth).

- Laux, S. (2018). “Unsex me here” – Brighter World, McMaster University. (Explanation of Lady Macbeth’s “unsex me” speech and gender performance).

- Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) (2020). Macbeth – Language and Themes, Learning Zone. (Educational analysis of “vaulting ambition” metaphor and nature imagery)

- Shakespeare Navigators (Weller, P., n.d.). Macbeth Theme: Manhood. (Detailed commentary on masculinity in Macbeth, including Macduff’s “feel it as a man” quote).

- Shakespeare Online (Mabillard, A., 2000). Glossary: “Look like the innocent flower, but be the serpent under’t.” (Gunpowder Plot medal allusion in Macbeth).

- Zitner, S. P. (1964). Macbeth and the Moral Scale of Tragedy. Journal of General Education, 16(1), pp. 20-28. (Criticism on “fair is foul” and moral ambivalence).

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

CollectionsContent relating to: “Macbeth”

Macbeth is one of William Shakespeare’s most studied tragedies, exploring ambition, power, fate and guilt in Jacobean Scotland. The play follows the rise and fall of Macbeth, a Scottish nobleman whose ruthless pursuit of the throne – encouraged by prophecy and his wife’s persuasion – leads to tyranny, paranoia and eventual downfall. Its themes of unchecked ambition, moral corruption and the supernatural have made it a timeless work still studied in schools and universities today. On this page you’ll find a range of resources to support your study of Macbeth: guides to key characters and themes, sample essays, and analysis of the play’s language and context. You can also explore more of our student-donated essays, browse expert-written examples, or read further insights on our academic blog. For additional tailored help, our essay writing services provide access to qualified UK experts who can support you with your assignments.

Related Articles