Evaluation of Humanitarian Aid Efforts of Natural Disasters

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Geography |

| ✅ Wordcount: 2487 words | ✅ Published: 18 May 2020 |

_______________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________________

The United Nations is an international organization which was established in 1945 and currently consists of 193 member states. According to UN Charter, its aim is to uphold global peace and security, cultivate/strengthen relations between countries, develop cooperation between countries to solve economic, social or humanitarian issues.

The fundamental structure of the non-refugee humanitarian coordination system was laid out by General Assembly resolution in 1991. However, this was revised in 2005, under the ‘Humanitarian Reform Agenda’. The major element introduced was the cluster system.

The cluster system consists of discrete organizations, some part of UN and some non-UN organizations which include intergovernmental, non-governmental, private sector and national partners. Each of these is allocated a specific sector of humanitarian action (water, health, shelter, agriculture, etc) to act in case of disasters. These sectors are delegated by the IASC (Inter-Agency Standing Committee), ensuring clarity of the roles and responsibilities of each organization to ensure maximum coordination, reduce duplication of projects and allow resources to be shared. This system’s first implementation was in 2005 and since been used in 30 countries worldwide.

Figure 1: The UN’s Cluster System – Diagrammatically illustrated; Image courtesy: UNOCHA HumanitarianResponse, 2019, link 13 in bibliography

Examples of humanitarian responses used in real life disasters will be used in this essay to show the positive and negative aspects of the cluster system of the UN. (The positive/negative aspect will be bolded and the disaster example will be underlined for easy identification)

In the Myanmar’s Nargis Cyclone, which occurred on 27th of April 2008, a total of 11 clusters were activated – Agriculture (FAO), Early Recovery (UNDP), Logistics (WFP), Protection (UNHCR), Emergency Shelter (IFRC), Health (WHO/MERLIN), Nutrition (UNICEF/GOUM), WASH (UNICEF), Emergency Tele-communication (WFP) and Food (WFP) (Kauffman & Kruger, 2010).

1 major negative aspect of the cluster system is it caused reluctance of the government to accept international aid. The UN cluster system calls for international aid from multiples nations/organizations. Governments are often disinterested in openly receiving assistance from these organizations due to political sensitivities, mainly to portray the image that the nation can manage disasters on its own to prevent criticisms from the political opposition parties. Also, ‘there is a particular resistance to the presence of foreign military personnel as it could be seen as an infringement of sovereignty’. (ABC News, 2018; directly quoted from link 1 in bibliography)

Exemplifying this issue with cluster systems, relief actions were halted in Myanmar after the Nargis Cyclone as its military personnel denied large-scale international assistance. ‘US President George W Bush said that an angry word should condemn the way Myanmar’s military rulers were handling the aftermath of such a catastrophic cyclone’ (Wikipedia,2019; directly quoted from link 2 in bibliography). Only 10 days after the Nargis cyclone were the efforts accepted by the government of Myanmar. This is comparable to Bali’s 2018 earthquake, where the Indonesian government instructed foreign aid workers to leave the quake zone, limiting the help offered by the cluster system. The set of rules put forward by the government is depicted below.

Figure 2: Rules for humanitarian relief – National Disaster Management Authority Indonesia, 2018 (Photo courtesy: ABC News, 2018)

The Australian Council for International Development’s chief, Marc Purcell, informed media he was surprised by this limitation on humanitarian relief due to the political sensitivity.

Also, the ‘Government of Myanmar was hesitant handing out visas to international aid workers and restricted in giving access to international aid workers….. restrictive in giving access for aid workers to travel to the Delta region which was one of the regions that was worst hit and this created difficulties in organizing and coordinating the response’. Also, ‘due to visa restrictions, OCHA was a late arrival to Myanmar’ (Trude Kvam Ulleland, 2013; directly quoted from link 3 in bibliography)

This shows three things. Firstly, the negative aspect of cluster system where governments are hesitant to allow it due to political sensitivities, delaying disaster response which costs lives. Secondly, how prominent of a role government’s intervention plays in cluster system activation, especially in sudden-onset disasters such as the denial of visas in the Myanmar’s Nargis cyclone project case, and how it can result in delays/inhibitions in humanitarian relief operations. The third negative aspect of the cluster system is how it can result in tensions between the government and the humanitarian relief organizations. This especially can be seen from the 2007 Pakistan floods, where the government insisted only a few clusters being activated to avoid the image of various countries helping it. However, there was a need to activate twelve and this caused tensions between the government and the involved actors.

As for the Myanmar’s Nargis Cyclone case, when aid items were donated by international aid agencies for the Sichuan earthquake in China, Myanmar’s government announced heavy persecution for its citizens who traded these items. This reflects the shortcoming of the cluster system of coordinating multiple aid agencies all around the world, causing political sensitivity for the government of the affected nation, in accepting their humanitarian help to avoid risking the image of their military calibre. A viable solution to this shortcoming would be pre-emptive treaties/agreements between nations to allow for international assistance being conducted in case of disasters striking in the future, to allow for smooth implementation of the procedures of the UN cluster system.

The fourth negative aspect of the UN cluster system is high turnover rates of cluster coordinators, causing gaps in predicted leadership. In Myanmar’s cyclone case, these coordinators had short-term contracts. For example, there were 5 different WASH cluster coordinators and their varying contract dates resulted in huge gaps between assignments in the Nargis Cyclone project. It also caused replacements of dedicated cluster coordinators (whose contract expired) with some others who managed assignments simultaneously as well as those that were not fully committed as the ones in their place before. The other challenge with this was the extra training needed to equip the new contractors to continue the assignment after the turnover of their original members. The lead coordinator of WASH in Myanmar’s Nargis Cyclone project stated that most cluster leads were not familiar with what a cluster is, so UNOCHA had to provide training first. It is evident that this causes delays and extra funding required in the training process, which seems to be a challenge in the cluster system.

Another challenge for Myanmar was the Cluster Coordination was more interested in long-term development rather than quick disaster response/relief. This is not always the best sought-after method for disaster management since long-term development is usually cost-driven while disaster management is time-driven.

Another significant negative aspect of the cluster system has traditionally been the lack of sufficient attendance in inter-cluster meetings. In the case of Myanmar’s cyclone, the main reasons were most materials used in the meetings being in English instead of Burmese which caused unclear communication hence disinterest in some local authorities to attend cluster meetings, as well as the fact that these cluster meetings being perceived to be ‘unfriendly’ by local authorities since they were designed for English speakers and expatriate staff. In the case of Haiti Earthquake, cluster meetings were held in English, restricting participation of local organizations that have French and Haitian Creole as their fundamental languages for communication. However, when GBV meetings for the Protection cluster were changed to French, local NGO participation increased. Another solution to strengthen the effectiveness of cluster meetings, is using translators which will allow cluster organizations to communicate information with local authorities before every meeting so that these authorities can prepare for the meeting and be motivated to be present.

A cardinal factor that undermines the effectiveness of the Cluster System is corruption. For example, USAID in Haiti allocated $270 million in 2013 for post infrastructure development following the damage from the Haiti earthquake. 40% was sent to American NGOs and 50% went to US organizations. ‘Chemonics International received $58 million claiming they would promote the recovery of Haiti and invest in ‘laying the foundation for long-term development’’ (Vinbury N., 2017; quoted from link 4 from bibliography). It was soon found out that Chemonics and USAID aimed to construct a biofuel company in Haiti with their funds, creating a ‘phantom aid’ situation overall. Weak administrative monitoring of the financing involved and gaps in the cluster system allowing corruption undermines its own effectiveness.

Another weakness of the Cluster Approach is the fact that disaster prevention has always been underfunded compared to emergency relief. For example, in the case of Haiti’s 2010 earthquake, many buildings that were reconstructed after the earthquake were made with cheap materials, further increasing the risk of a second disaster in case of another earthquake.

The final negative aspect of the cluster approach to humanitarian relief in disasters is the lack of knowledge of international aid organizations of local culture and lifestyles, which can cause wastage of funds spent on building capital for long-term development. For example, between 2011 and 2013, the Caracol EKAM project took charge of housing development in Haiti post-earthquake to restore infrastructure. The budget for design and construction was estimated to be US$31.5 million. The implementing partners were US contractors, CEEPCO contractors, THOR construction and Global communities, all being non-Haiti based companies. The end result was “a total mess, a total failure with very poor planning” (Melinda Miles, 2015; directly quoted from link 4 in bibliography) The homes have been called ‘culturally inappropriate’ and have resulted in plenty being unoccupied and empty. “Donors are not doing their homework to understand preferences and lifestyle of Haiti’s population” (Gesly Leveque, 2015; directly quoted from link 4 in bibliography)

However, one positive aspect of the UN cluster system is it minimizes gaps and overlaps in humanitarian roles in global disaster responses, by allocating specific sectors of humanitarian actions for each organization. This is proved true in the case of the Myanmar Nargis Cyclone. According to the cluster approach’s second evaluation phase, ‘it was evidenced in Myanmar that overall duplications were eliminated and gaps were identified due to the cluster approach. The evaluation team found that due to this, it resulted in more efficiency and wider coverage’ (Trude Kvam Ulleland, 2013; directly quoted from link 3 in bibliography).

The second positive aspect of the cluster system is it enhances communication between humanitarian aid workers and the sector representatives/leaders in the country to sort out issues. In the case of Nargis Cyclone, the cluster approach evaluation phase 2 concluded that the cluster approach did indeed strengthen communication. Humanitarian organizations from each cluster played an intermediary role between the government and NGOs. Special meetings were arranged which were set up for each organization from the cluster representing a specific sector, to talk with local authorities responsible for that same sector (e.g. WASH/Education). The benefits of this are the ability to exchange ideas for policies and guidelines for humanitarian aid for each sector, straightforward process of seeking approval from the local authorities to carry out relief mechanisms and simplifying the process by knowing to who to talk to.

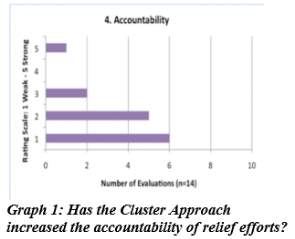

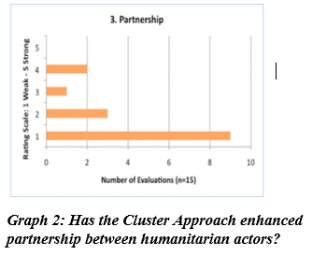

Here are graphs that show the result of 18 evaluations throughout the humanitarian relief process in Myanmar. Majority of the evaluations are in favour of the cluster system, depicting its effectiveness of having an appropriate structure for improving the coordination of humanitarian relief. (Graphs extracted from link 5 in bibliography)

Here are graphs that show the result of 18 evaluations throughout the humanitarian relief process in Myanmar. Majority of the evaluations are in favour of the cluster system, depicting its effectiveness of having an appropriate structure for improving the coordination of humanitarian relief. (Graphs extracted from link 5 in bibliography)

For the 3rd positive aspect of the cluster approach, a closer look is needed at the humanitarian crisis management project in Northern Uganda, where 90% of the population are displaced from homes. The protection cluster in northern Uganda during humanitarian crisis management in 2006 found organizations duplicating programs in the same region. This immediately was followed by a cluster meeting in the protection sector, and an agreement was made to move the program to an area where much more coverage is desperately needed. This is an example of the effectiveness of cluster meetings in successful team coordination and planning of humanitarian responses.

Also, during Somalia Drought 2015-2019, UNICEF noted gaps in its WASH cluster and became more active in recruiting new local NGO partners. This shows how the cluster approach separates specific sectors for humanitarian response and makes easier to track progress of each sector for the overall success of the project and shows how clusters help actors to decide which gaps to fill.

The cluster approach, between 2004 and 2006, has increased levels of humanitarian funding by 56% and between 2005 and 2006, has increased the number of actors by 32%, which is a positive impact on global humanitarian management. This could be a result of the awareness created by the cluster approach at a global level, through the coordination of various organizations worldwide.

Finally, the last note-worthy positive aspect of the cluster system is, it ensures response capacity is in place and that leadership in carrying out humanitarian responses are strengthened through inter-organizational coordination. This can be seen from the humanitarian project during Somalia’s drought in 2011, where the ‘nutrition’ cluster lead coordinated with all the organizations in that cluster to identify key geographical areas where coverage was small and eventually altered numbers of personnel in each location to provide food for the affected people.

Bibliography

- Indonesia tells independent foreign aid workers to leave quake zone. (2018). Retrieved 13 July 2019, from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-10-09/indonesia-tells-independent-foreign-aid-workers-leave-quake-zone/10357204

- Cyclone Nargis. (2019). Retrieved 21 July 2019, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyclone_Nargis

- Kvam Ulleland, T. (2013). The Cluster Approach for Organizing Emergency Response: A case study of Myanmar and Haiti (2008). Retrieved 12 July 2019, from http://bora.uib.no/bitstream/handle/1956/7763/116215926.pdf;sequence=1

- Vinbury, N. (2017). Cluster Approach: Gaps and shortcomings in UN coordination of humanitarian actors in post-earthquake Haiti and implications for policy concerns of the New Humanitarian school of thought. Retrieved 12 July 2019, from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e995/5d864818898ad610e5710b581e73d2ddec1a.pdf

- Humphries, V. (2013). Improving Humanitarian Coordination: Common Challenges and Lessons Learned from the Cluster Approach. Retrieved 13 July 2019, from http://sites.tufts.edu/jha/archives/1976

- Stoddar, D., Harmer, A., Haver, K., Salomons, D., & Wheeler, V. (2007). Cluster Approach Evaluation. Retrieved 13 July 2019, from https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/4955.pdf

- Boon, L. (2012). The Cluster Approach: Working Towards Best Practices in Humanitarian Response. Retrieved 13 July 2019, from https://www.du.edu/korbel/crric/media/documents/logan_boon.pdf

- Parihar, G. (2007). The UN Cluster Approach in the Pakistan earthquake response: an NGO perspective – ODI HPN. Retrieved 21 July 2019, from https://odihpn.org/magazine/the-un-cluster-approach-in-the-pakistan-earthquake-response-an-ngo-perspective/

- The Cluster Approach. (2007). Retrieved 17 July 2019, from https://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/tools/manuals/who_field_handbook/annex_7/en/

- Jamal, A., Herrera, J., & Kiani, M. (2019). Cluster Approach (IASC). Retrieved 15 July 2019, from https://emergency.unhcr.org/entry/61190/cluster-approach-iasc

- Who does what? | HumanitarianResponse. (2019). Retrieved 16 July 2019, from https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/fr/coordination/clusters/who-does-what

- What is the Cluster Approach? | HumanitarianResponse. (2019). Retrieved 17 July 2019, from https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/about-clusters/what-is-the-cluster-approach

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal