Assessment of Market Power

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Economics |

| ✅ Wordcount: 1599 words | ✅ Published: 20 Nov 2017 |

A firm has market power if it finds it profitable to raise prices above marginal costs[1]. Identifying the profitability of firms can assist in assessing market power, as both are defined in terms of firms’ ability to raise prices consistently and profitably above competitive levels. This is not a straightforward process due in part to genuine reasons for excess profits and difficulties in identifying the competitive price level but also due to the many other determinants of market power.

In the model of perfect competition, price equals marginal cost. Understanding a firm’s cost structure and the price it charges is therefore the most direct way of measuring market power. It is on this basis that the Lerner Index was developed, which examines the mark up of a firm specific price above its marginal cost. Direct application is problematic however due to the difficulty surrounding the estimation of marginal cost while it tends to be somewhat controversial to focus primarily on the profitability of firms when analysing market power[2].

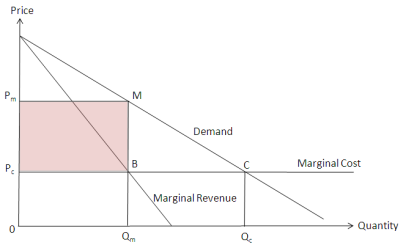

The representation below of profits generated under the economic models of perfect competition (c) and monopoly (m) illustrates that a perfectly competitive industry produces at point C whereas a monopolist will maximize profits by producing at point M (derived from point B). Evidently, zero profits are generated in the model of perfect competition. By comparison, a monopoly (i.e. the most extreme form of market power) generates significant profits when market power is exercised, as denoted by the shaded area.

Figure 1: Profit Maximisation under Perfect Competition and by Monopoly

A monopolist’s ability to enjoy profits by pricing above the competitive level is dependent on the presence of high barriers to entry such that other firms do not constrain the monopoly’s profits by entering the market or by the threat of entry. Any exercise of market power will be limited by its elasticity of demand implying that if consumers are unwilling to pay at Pm, a monopolist may be forced to price closer to Pc.

Market power tends to decrease with the number of firms in the industry[3]. However, from an economic theory perspective, the net effect of market power on welfare is not clear-cut due to the need to draw conclusions from the trade-off between allocative efficiency and productive efficiency. A reduction in market power usually implies lower consumer prices but this does not infer that the larger the number of firms the higher the welfare as an increasing number of firms can impact on productive efficiency due to the duplication of fixed costs, for example.

As high profits tend to correspond to the presence of market power, an assessment of a firm’s profitability may be thought of as being a good indication of the degree of market power present i.e. weak competition is present if a firm is earning profits in excess of a reasonable rate of return. This is a flawed approach however, without accounting for the following potential sources of economic profit, as outlined by Bishop/Walker:

- Schumpeterian rents – rewards for taking risk and innovation[4]; and

- Ricardian rents – rewards to a competitive advantage such as superior efficiency or better management.

These are not anticompetitive concerns and represent genuine reasons for profits diverging from a reasonable rate of return. For example, entrepreneurs tend to take risks on the premise that if they are successful, substantial profits will follow. Moreover, a firm earning excess profits following enhanced efficiencies does not do so by restricting output as illustrated in Figure 1, rather it does the opposite. Furthermore, while profits may exceed the cost of capital in the short run due to economic cycles and windfall gains, these are not necessarily related to market power or anticompetitive practices[5]. Conversely, an inefficient firm may experience profits below marginal costs, which may serve to conceal a competition problem in the market if profitability was considered in isolation.

When excess profits are found to result from market power, the question arises as to what constitutes an excessive return. This is one of many conceptual issues surrounding the application of metrics such as the internal rate of return and net present value that can be used in examining the economic profitability of firms. Thus, the aforementioned intricacies have led to the view that “profitability measures can provide a good answer to the wrong question and much less a good answer to the question we really want to answer”[6].

A perfectly contestable model emphasises the important influence that barriers to entry have in a market power analysis. In this model there are no barriers to entry or exit, implying that the threat of new entrants can discipline a monopolist firm to set prices at an efficient level. The model is often considered purely theoretical, as it requires the absence of sunk costs in addition to competitors being able to enter the market earn a profit and exit before the incumbent can adjust prices[7]. The UK Competition Commission did demonstrate however that the concept can be applied in a real world setting[8].

As market power is determined by the level of competitive constraints facing a firm, consideration of barriers to entry and expansion might appear to constitute a sufficient analysis. This is however an inadequate assessment of market power as the absence of competitive constraints does not necessarily imply that firms can raise prices above the competitive level. Profits should at least be assessed to validate a preliminary analysis, as according to Neils/Jenkins/Kavanagh, “persistent and high profits are consistent with the presence of entry barriers”.

The various factors required to exert market power can be illustrated with a basic economic model of a static dominant firm with a large market share and a competitive fringe with exogenous behaviour. It assumes that competing firms can expand output while barriers to entry remain[9]. The degree to which an individual firm can raise prices above marginal costs depends on its firm specific elasticity of demand (εf), which is derived as follows:

(1) εf = (εd + (1-S) εr) / S[10]

where, εd is the market elasticity of demand; S is the firms market share; and εr is the elasticity of supply of rival firms

Market shares

A high market share is likely to result in a lower elasticity of demand faced by a dominant firm but it does not necessarily infer market power. As above, market shares are just one component that determines εf. An assessment of other industry characteristics is therefore required, possibly supplemented with a profitability analysis, in order to gain more insight into the dynamics of the industry.

Barriers to entry and expansion

Similarly, the extent of barriers to entry and expansion are some of several components that determine the market power of the dominant firm, εf. As the assessment of market power requires an understanding of the size of these barriers, as in Aberdeen Journals’, consideration should be given to potential factors that increase barriers such as switching costs, lock-in effects and network externalities. The history of an industry, such as reputations, may also prove useful in ascertaining the extent of εr.

Relative position of competitors

Valuable insights into the nature of competition can be obtained from static oligopoly models, which contain a standard assumption that the choice of rival competitors is fixed, either in prices (Bertrand) or quantities (Cournot). Market power is likely to be more prevalent and competition less intense in Cournot type markets as firms compete by quantity setting, whereas firms in Bertrand type markets compete on price alone and therefore the effect of market power via the reduction in output, as illustrated in Figure 1, does not arise.

Buyer power

Buyer power arises when large consumers negotiate with its supplier in order to lower prices under the credible threat that it could easily source its supply by an alternative means. The market power of what would otherwise be a dominant firm may be restricted by countervailing buyer power, as in Italian Flat Glass. A firm is in a better position to exert market power if it faces a large number of displaced consumers or buyers than if it faces one or a few strong buyers[11].

Market elasticity of demand

The market elasticity of demand εd has a significant influence on the extent of market power as shown in Figure 1 and further demonstrated in equation (1). In this model, the higher the elasticity of demand (e.g. laptops) that a monopolist faces, the higher its market power is likely to be compared to a monopolist firm with a relatively lower elasticity of demand (e.g. table salt). Examining the market elasticity of demand also helps to ensure that the market has been correctly defined with regard to potential substitutes.

Products market

This model is also based on a market of homogenous products, which when relaxed for differentiated products, reduces the firm’s elasticity of demand in line with the degree of differentiation between products. This has the effect of increasing its market power.

Each of these factors required to exert market power are illustrated in Figure 2. While each factor can be informative in isolation, a much more comprehensive analysis is required to identify market power in a properly defined market and may require a profitability analysis to assess the extent of any difference between P and P* above. If the gap is significant, it is then necessary to examine if this has resulted from the exertion of dominance or from more genuine circumstances.

Figure 2: Dominant firm with a competitive fringe model[12]

An important distinction between the price taking competitive fringe and the dominant firm is that the latter has lower marginal costs (Marginal CostD

The competitive price is much higher in this model, due to the lower costs of the dominant firm, even though they are not sufficiently low to result in a socially efficient outcome at Q*. According to Geradin et al, the competitive price level is virtually always impossible to calculate on both conceptual and data grounds while Bishop/Walker emphasise how much easier the application of competition law would be if this was not the case.

In an analysis of market power, it would be unwise to focus on the profitability of firms, or other factors such as market shares, which can be meaningless without a comprehensive assessment of competition in the market. It is important that appropriate weighting is attributed to the aforementioned factors and that the economic analysis does not simply constitute an incoherent checklist approach.

Bibliography

S Bishop and M Walker: “Economics of EC Competition Law: Concepts, Applications and Measurement” (Third Edition, Sweet & Maxwell, 2010)

Charles Rivers Associates: “Competition Memo – The CC Decision on North Sea Helicopter Services”, (originally published by Lexecon Ltd, 2000)

J Church and R Ware: “Industrial Organisation: A Strategic Approach” (McGraw-Hill, 2000)

Editors of American Bar Association, “Market Power Handbook: Competition Law and Economic Foundations”, (American Bar Association, 2005)

D Geradin, P Hoder, F Louis, N Petit and M Walker: “The Concept of Dominance in EC Competition Law”, Global Competition Law Centre, College of Europe (2005)

P Grout and A Zalewska: “Profitability Measures” Issues in competition law and policy ABA Section of Antitrust Law, (Collins 2009)

L Kaplow and C Shapiro: “Antitrust” Handbook of Law and Economics, Vol. 2: 1077-125, (Elsevier, 2007)

W Landes and R Posner, “Market Power in Antitrust Cases”, Harvard Law Review, Vol. 94(5): 937-996 (1981)

M Motta: “Competition Policy: Theory and Practice”, (Cambridge 2004)

G Myers: “Barriers to Entry”, Teaching Business and Economics 1:124-131 (1993)

G Niels, H Jenkins and J Kavanagh: “Economics for Competition Lawyers”, (Oxford 2011)

OXERA: “Assessing proï¬tability in competition policy analysis” Economic Discussion Paper 6, prepared for the Ofï¬ce of Fair Trading (2003)

R Whish and D Bailey: “Competition Law” (Seventh Edition, Oxford, 2012)

1

[1] Church/Ware (2000)

[2] Profitability analysis is much more a feature of UK Competition law than it is in the EU or US, according to Bishop/Walker (2010), despite United Brands implying a potential role in Europe for profitability analysis in excessive pricing cases.

[3] Motta (2004)

[4] E.g. Glaxo and its profits from Zantac following patent protection

[5] Oxera (2003)

[6] Grout and Zalewska (2009)

[7] Myers (1993)

[8] Both Bailey/Whish (2012) and Bishop (2000) cite the UK CC decision in CHC Helicopter Corporation/Helicopter Services Group ASA as an example of a real world setting in which a merger that would create a duopoly was cleared on the basis that the market was contestable.

[9] Rentokil provides a good example of this model in which it had 70% of the UK market in the 1980s and competed with over 200 firms, neither of which had more than 2% market share.

[10] Kaplow/Shapiro (2007) and Landes/Posner (1981)

[11] Motta (2004)

[12] Church/Ware (2000) [emphasis added]

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal