The Yellow Book: Textual Condition and Image Cultivation

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Arts |

| ✅ Wordcount: 3354 words | ✅ Published: 23 Sep 2019 |

The Yellow Book: Some Perspectives on Its Textual Condition and Image Cultivation

Among the incredible diversity of nineteenth century periodicals, The Yellow Book has long stood out, which is reflected in the continuous scholarly interest. Since the material turn in literary studies in the 1970s, more attention has been paid to the material context of literary objects. This essay argues that a close reading of the “textual condition” of the Yellow Book offers a new perspective on this fin-de-siècle periodical. Thanks to Whistler’s donation of his library to the library of the University of Glasgow, the author of this essay had access to the complete set of the thirteen volumes of The Yellow Book. This essay seeks to analyse a selection of the material context surrounding The Yellow Book, which offers an insight into the various perspectives on self-presentation. These will include the layout, the price and the advertisement material in order to place The Yellow Book in its wider cultural context. This is followed by an analysis of a series of portraits, “The Bodley Heads”.

Published for the first time in April 1894 by John Lane and Elkin Matthews as the publishers of the Bodley Head, The Yellow Book has gained a status of being the materialization of the “Yellow Nineties”. Even before the publication of the first issue the magazine has started moulding its own image and in the last hundred years both contributors to the magazine and scholars have shaped the representation of the so-called notorious Yellow Book. The essay by Marcovitch follows the course of the development of the research surrounding The Yellow Book since its publication, from the “Study in Yellow” by Katherine Mix published in 1960 to more recent research focusing more on the diversity and a sense of experimentation of the Yellow Book. The focus has shifted from a male-centred magazine dominated by the art-work by Aubrey Beardsley and figures such as the editor Henry Harland and Max Beerbohm, to studies of the contributions by female writers. The role of Ella D’Arcy as contributor and the sub-editor of the Yellow Book, and contributions by writers such as George Egerton (Mary Chavelita Dunne Bright), Charlotte Mew and Evelyn Sharp have been included in the studies of the Yellow Book, highlighting its collaborative approach.

The increasing interest in the materiality of books has caused a shift in focus to include this field of studies, which widens the scope of the experience of written texts and challenges the peripheral role assigned to the context. In his work Seuils, which translates as threshold, Gérard Genette points to the importance of the paratext, information that “surround[s] [a literary object] and extend[s] it, precisely in order to present it, in the usual sense of this verb but also in the strongest sense: to make present, to ensure the text’s presence in the world, its reception and consumption in the form” (1). The paratext “constitutes a zone between text and off-text, a zone not only of transition but also of transaction: a privileged place of a pragmatics and a strategy, of an influence on the public” (Genette 2). In other words, the production of meaning created by the paratext is a continuous process, “a zone of transition”. For this essay the notion of process and the literary object’s continuous (“and open-ended”) production of meaningis of great importance. By naming the work threshold, Genette emphasizes the secondary nature of the paratext, subordinate to the content of a literary object, the text “as such”. This essay tries to challenge this argument by providing analyses of the context which contributes to the production of meaning of The Yellow Book.

In addition to the linguistic content of periodicals, the information surrounding texts gains in importance. “Every literary text that descends to us operates through the deployment of a double helix of perceptual codes: the linguistic codes, on one hand, and the bibliographical codes on the other” (McGann Condition 70). Both codes are inextricably linked and contribute on equal terms to the production of meaning. The “textual condition” is a term coined by Jerome McGann, a leading scholar in the textuality of books. His analysis focuses on the importance of the sociocultural conditions in which texts have been produced, which are subject to continuous development:

The textual condition’s only immutable law is the law of change. It is a law, however, like all laws, that operates within certain limits. […] The law of change declares that these histories will exhibit a ceaseless process of textual development and mutation – a process which can only be arrested if all the textual transformations of a particular work fall into non-existence. To study texts and textualities, then, we have to study these complex (and open-ended) histories of textual change and variance (Condition 9)

Being subject to constant change, the textual condition depends largely on the scholar analysing it. As mentioned in the beginning of the essay, the scholarly work on The Yellow Book has shown a diversity of perspectives. The first essay which focused on the material aspect of what McGann later called the textual condition was by Linda Dowling, “Letterpress and Picture in the Literary Periodicals of the 1890s”, published in 1986. She analysed the relationship of illustration and text in order to “illuminate the complex intertexture of commercial and aesthetic motives so characteristic of fin de siècle periodicals and artistic life generally” (131). This highlights the importance of conjoining the meanings of the visual and the textual level of a literary object. One example is the inclusion of art-work in The Yellow Book. The editors of The Yellow Book announced in the prospectus of the first Volume that “the pictures will in no case serve as illustrations to the letter-press, but each will stand by itself as an independent contribution”. The attempt to separate the illustrations, from the second issue onwards they are called ‘Art’, from the texts as such, only works to a certain extent. Even though the art work is presented independently by giving it one page with the details of the artist and a protective sheet of tissue paper, the art work is always embedded in the neighbouring literary works.

The importance given to the external presentation of The Yellow Book underlines its significance. “[T]he physique of the ‘document’ has been forced to play an aesthetic function, has been made part of the ‘literary work’. […] The physical presentation of […] printed texts has been made to serve aesthetic ends” (McGann Socialisation 70). The context and the outer appearance of a book is not an innocent storage of information, but part of the process of representation. To gain a more complete picture of The Yellow Book, this essay’s aim is to filter some aspects of the extratextual elements, because the analysis of the textual condition “draw[s] our attention to that quality of self-embodiment that is so central to the nature of texts” (McGann Condition 14). One essential aspect for this essay is McGann’s socialised and collaborative view of the text. As mentioned before, recent critical work on The Yellow Book has painted a much collaborative and eclectic picture of it. During the 1890s The Yellow Book became an experimental platform, introducing a growing readership to a variety of writing and art, ranging from ‘New Women’ writers such as George Egerton and Evelyn Sharp to more conservative writers such as Henry James, and from Aubrey Beardsley and Walter Sickert to artists such as Frederic Leighton or Wilson Steer. It was “the clash of the “old” and the “new” that characterises fin-de-siècle cultural politics more generally is played out in microcosm in the pages of The Yellow Book” (Ledger 9). Some writers and artists contributed regularly to the Yellow Book while others only appeared once. As Oscar Wilde commented on a lecture by Whistler: “An Artist is not an isolated fact; he is the result of a certain milieu and a certain entourage” (Kooistra 34). The Yellow Book is not just the product of its editors, but of a wider cultural and social entourage and to understand this context is a way of having a well-rounded picture of the magazine.

Ella D’Arcy calls this entourage of The Yellow Book the “Cromwell Road Circle” in the Reminiscences she published in the 1920s. “Never were there such as evenings as those long-ago evenings in the Cromwell Road”, where a large number of the contributors of The Yellow Book met usually on Sunday evenings. Another retrospective commentary was written by Evelyn Sharp for the Manchester Guardian in 1924, “A Group of the Nineties”, as an obituary for of one its contributors, Oswald Sickert. Among those mentioned are Henry Harland, Ella D’Arcy and Richard Le Galienne and “there too came others, who were fast “arriving”: Aubrey Beardsley of course, already looking as if he had not the physical strength to draw his next cover” and “now and then came one or two of the recognised great, straight from the world of letters in which they had already arrived”. The group was composed of both established writers and newly discovered ones, forming a diverse and hybrid community.

Thus it was The Yellow Book’s “character and form [which ]are notable for their transgressive hybridity: it was a quarterly, but one that was artistic and literary rather than just based on weighty heavy journalism” (140 Turner). In the prospectus of the first issue in April 1894, it says:

The aim of the Publishers and Editors of The Yellow Book is to depart as far as may be from the bad old traditions of periodical literature, and to provide an Illustrated Magazine which shall be beautiful as a piece of bookmaking, modern and distinguished in its letterpress and its pictures, and withal popular in the better sense of the word. (Yellow Book Prospectus)

This statement reveals the importance of self-presentation and promotion. Published a few months before the first issue of the Yellow Book was released, this prospectus announces the publication by distancing itself from the “old traditions” and hoping to be “popular in the better sense of the word”, while still upholding a certain artistic standard. This reflects the context of the rapidly changing publishing industry, in which The Yellow Book sought be find its distinct niche as a high-quality literature and arts magazine all the while needing to be financially sustainable for John Lane and the Bodley Head. The Bodley Head defined itself as “Publishers and Vendors of Choice & Rare Editions in Belles Lettres”. In its form and content, it aimed to be “modern and distinct” as announced further in the prospectus. It “chiefly published serious and experimental writing in handsome book designs at relatively cheap prices. Printing runs were small as the books were being offered to a special audience […] To be a Bodley Head author, or reader, defined you as a certain type of person – aesthetic and modern” (McGann Riders 78). This not only applied to the books the Bodley Head published, but also to the magazines.

As the name of the magazine suggests, The Yellow Book is bound in yellow cloth, alluding to the “yellow” French novels, which sparked much controversy during their time. With black illustrations printed on the front cover it ensured its visibility, and later on, recognisability. Due to its distinctive design it attracted attention at the bookshops, the libraries and the railway bookstalls where it was sold. The cover as such was of robust quality and the high-quality paper set The Yellow Book apart from other periodicals during its time, which set their focus on reducing the production costs in order to increase their printing numbers. Costing 5 shillings it was among the higher priced publications but was not as expensive as the three-decker novel commonly sold at that time. The higher cost implies an upper-middle-class to upper-class readership. Genre-wise it was very diverse, reaching from essays to drama but its main focus was on short stories and poetry. “It will publish no serials; but its complete stories will sometimes run to a considerable length themselves. Thus, the tiresome “choppy” effect of so many magazines will be avoided” (Yellow Book Vol.1 Prospectus). Choosing the short story as the most prominent genre ties in with The Yellow Book’s attempt to “have the courage of its modernness” and can thus be seen as a precursor of the ‘little magazines’ in the early 20th century.

Intentionally the editors decided to name it a ’book’, emphasising its quality as a publication and as literary magazine.

It will be a book – a book to read, and placed upon one’s shelves, and read again; a book in form, a book in substance; a book beautiful to see and convenient to handle; a book with style, a book with finish; a book that every book-lover will love at first sight; a book that will make book-lovers of many who are now indifferent to books. (The Yellow Book Vol.1 Prospectus)

Paratextual elements, such as the minimalistic mis-en-page with the catch word at each right-hand corner of a page, function as the brand identity of the periodical. Compared to other publishers focusing on Belles Lettres the Bodley Head was known for its “crisp contemporaneity”, promoting readability by stripping off any ornamental designs (McGann Riders 12). Those were commonly seen at the Kelmscott Press, a publishing house connected to William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement. It is a question of recognisability, which in turn leads to the larger readership needed for economic profitability. In order to find a niche on the competitive market of fin-de-siècle periodicals it was crucial to develop a brand identity.

Even though The Yellow Book was known for its modern approach in terms of its layout, some aspects can be traced back to inspiration by William Morris, who in turn was inspired by medieval traditions. Both publishing houses “had begun to work consciously with the spatial features of the page and the book as they might be resources for poetic effects” (McGann Riders 79). The mis-en-page followed the design of medieval manuscripts, which Morris was inspired by; he “stressed that there should be a difference of 20 per cent between each margin on a page, with the narrowest being the inside edge, followed by the top, the outside edge, and finally the bottom edge being the largest” (Brooker 71). And just like in the Century Guild Hobby Horse it used the Caslon old face, a type face which was rarely seen in the increasingly commercialised printing industry of the 1890s. This indicates a carefully chosen counter position against the mass publications, which focused on quantity rather than quality.

The catch word added at the bottom of every page sparked some discussion among the contributors of The Yellow Book. Linda Dowling saw them as a “deliberate anachronism: they are of no practical use, but their expressive function is to link the periodical to the world of fine books and the history of printing, specifically, the eighteenth-century world of William Caslon” (126). According to Hamerton, who wrote a “Criticism of Vol I” in the following issue, both John Davidson and he were not in favour of reinstating this “detestable old custom”, considering it an intolerable and unnecessary supplement (Yellow Book Vol.2 182). The discussion of these seemingly small details in a critique of The Yellow Book reveals that even the smallest bibliographical code is part of the representation and image cultivation.

Another interesting visual aspect of The Yellow Book are the diverse portraits. They not only differ in style, but also in the people they depict. On the one hand The Yellow Book included portraits of well-known authors like Henry James, George Moore or George Egerton and on the other hand also a considerable number of well-known stage actresses. As noticed by Linda Dowling in her article: “Portraits were another central stand of decorative illustration, which offered a crucial way to acquaint the public with its public figures” (112). In a time, when it became more common to see celebrities of all areas to be depicted in periodicals, The Yellow Book participated in this movement by including a series of portraits.

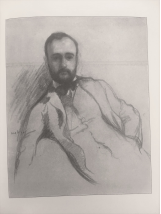

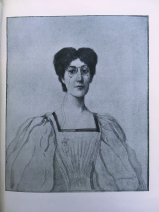

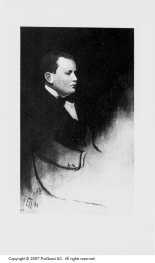

One series stands out particularly, namely one called “The Bodley Heads”, which runs from the fourth volume to the penultimate issue and depicts five different authors. The first illustration of a “Bodley Head” is of Richard Le Galienne made by Walter Sickert published in Volume IV, who was not only a frequent contributor to The Yellow Book and had all of his works published at The Bodley Head but also had a significant role as a reader for the firm (Nelson 271). The second one in Volume IV is of John Davidson by William Rothenstein, a poet who was part of the Rhymers’ Club and was known for his anti-decadent perspectives. “Bodley Heads No. 3” was of George Egerton and it was published in Volume 5, drawn by the Scottish painter E.A. Walton who was a great admirer of Whistler. She was the first female author to be depicted in The Yellow Book who was already well-known due to the Keynotes, one of the most successful series published by The Bodley Head in 1893 with over 6000 copies printed. Bodley Heads No. 5 and 6 (No. 4 was skipped) were portraits of G.S. Street, drawn by Francis Howard and Evelyn Sharp was just like George Egerton depicted by E.A. Walton. All of those portrayed as the Bodley Heads have had books published at The Bodley Head. The editor’s decision to publish these portraits was not only conducive to business for The Yellow Book itself to promote its writers, but also for the publishing house as such. In creating this series, the reader was familiarized with a selection of authors The Bodley Head sought out as representative of the publishing house.

The inclusion of portraits, the diversity of editorial decisions, the mise en page, type and quality of the binding and the paper, alongside other elements of the bibliographical codes, which have not been discussed in this essay for reasons of brevity, function as markers in The Yellow Book which create meaning and a certain image. By applying theories of Gérard Genette and Jeremy McGann this essay has sought to challenge the secondariness of the bibliographical code(s). It is arguably through the analysis of the context of a literary object that we can better understand the workings of these objects, in this case The Yellow Book. The present paper has only scratched the surface of what could be a more extensive research, one which could involve a comparative study of the bibliographical code(s) of several periodicals.

Illustrations from top left to bottom right: Bodley Heads: No.1 Richard Le Galienne by Walter Sickert, No. 2 John Davidson by William Rothenstein, No. 3 George Egerton by E.A. Walton, No. 5 G.S. Street by Francis Howard, No. 6 Evelyn Sharp by E.A. Walton

Bibliography

- Harland, Henry, et al, eds. The Yellow Book. London: The Bodley Head, 1894-1897. 13 Vol.

- Brake, Laurel. “Aestheticism and Decadence: The Yellow Book(1894-7), The Chameleon (1894), and The Savoy(1896).” The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines Volume 1. Eds. Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2010. 76-100.

- Brooker, Peter and Andrew Thacker, eds. The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2010.

- Dowling, Linda. “The Letterpress and Picture in the Literary Magazines of the 1890s.” The Yearbook of English Studies 16 (1986). 117-131.

- Fisher, Benjamin. “Ella D’Arcy Reminiscences.” English Literature in Transition 37.1. (1994). 28-32.

- Genette, Gérard. Paratext: Threshold of Interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997.

- Ledger, Sally. “Wilde Women and the Yellow Book: The Sexual Politics of Aestheticism and Decadence.” English Literature in Transition 50.1 (2007). 5-26.

- Kooistra, Lorraine Jantzen. The Artist as Critic : Bitextuality in Fin-de-Siècle Illustrated Books. Aldershot: Scolarpress, 1995.

- Marcovitch, Heather. “The Yellow Book: The Reshaping of the Fin de Siècle.” Literature Compass 13.2. (2016). 79-87.

- Nelson, James. The Early Nineties: A View from The Bodley Head. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1971.

-

McGann, Jeremy. The Textual Condition. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1991.

- —. The Black Riders: The Visible Language of Modernism. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1993.

- —. “The Socialisation of Texts.” The Book History Reader. Eds. David Finkelstein and Alistair McLeery. London: Routledge, 2006. 66-74.

- Sharp, Evelyn. “A Group of the Nineties.” The Manchester Guardian. 19. Jan 1924.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal