Capstone Project to Improve Safety in Commercial UAS Flights

| ✓ Paper Type: Free Assignment | ✓ Study Level: University / Undergraduate |

| ✓ Wordcount: 6826 words | ✓ Published: 22 Apr 2021 |

Abstract

The research presented in this graduate capstone project for the Master of Science in Aeronautics, Unmanned Aerospace Systems concentration provides a mixed-methods analysis of unmanned aerial system (UAS) mishaps and incidents that have been classified by contributing human factors using the Department of Defense (DoD) Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS) version 7.0. Three politically and operationally diverse government incident reporting systems were coded with contributing human factors of acts, preconditions, supervision, and organizational influences to determine if formal training requirements show an association with reduced human factors mishaps. The U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS), Australian Civil Aviation Safety Authority’s (CASA) Air Transportation Safety Board (ATSB) mishap system, and the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) Office of Aviation Services (OAS) Safety Communiqué (SAFECOM) database were compared using Spearman’s correlation coefficient (= 0.05). The HFACS-coded ASRS reports did not result in strong positive correlation with either the ATSB or SAFECOM systems, but a strong positive monotonic relationship (69%, = 0.003) was observed between the ATSB and SAFECOM reporting systems. A qualitative analysis showed a significant outlier for the low incidence of training-related mishaps in the DOI compared to reports from ASRS and the ATSB. An industry-led training standards development and reporting process is recommended to verify the impact of formal training and encourage the safe integration of UAS into the U.S. National Airspace System.

Keywords: human factors, formal training, unmanned aerial systems, safety reporting, Australia, Department of the Interior

Project Title

Training to influence attitude and situation awareness

Approved Proposal

The research presented in this proposal will be used to make a practical training recommendation that addresses reported incidents of airspace incursions, deviation from clearances, procedural deviations, and other unsafe acts as reported by remote pilots and air traffic controllers (ATC) in the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) database.

Scope

The research presented in this graduate capstone individual project will examine the potential for a link between the regulations in Australia that require practical UAS training and the incidence of unsafe acts by unmanned aircraft system (UAS) operators in the United States. A human factors analysis and classification system (HFACS) will be used to standardize the data used in this research. A smaller-scale comparison will be made of manned and unmanned historical aviation incidents that occurred within the Department of the Interior (DOI), which requires practical training for any personnel that wishes to utilize UAS. Determining specific training methodologies, syllabi, or suitable training platforms is outside the scope of this research.

Objective

The objective of this research is to improve the safety and public perception of commercial UAS operations by providing examples of successful implementation of UAS training in another country and in a large domestic government organization. Training will not prevent all forms of unsafe acts by remote pilots, but the hypothesis to be tested is that training does influence a specific type of error related to attitude and situation awareness.

The research will be conducted using mixed methods: utilizing HFACS taxonomy to categorize reports of unsafe acts and relate categorical outliers and testing the hypothesis with quantitative statistical analysis. The hypothesis is that a no statistically significant correlation ( > 0.05) will exist between a UAS operational system that does not require formal training and two other systems that do. To verify the hypothesis, a second hypothesis is that a statistically significant correlation will exist between two UAS operational systems that require formal practical UAS training.

Program Outcomes

PO #1: The student will be able to apply the fundamentals of air transportation as part of a global, multimodal transportation system, including the technological, social, environmental, and political aspects of the system to examine, compare, analyze, and recommend conclusions.

This program outcome will be addressed by examining, comparing, and analyzing the political difference between training requirements for the commercial U.S. FAA Remote Pilot Certificate (RPC) and Australia’s Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) Remote Pilot License (RePL) and recommend conclusions. The growth of the UAS industry and its impact on the multimodal transportation system will be summarized with analysis of the technological solutions that have been proposed to reduce the social and environmental implications of a UAS colliding with a manned aircraft and the public perception of UAS as part of the global air transportation system.

PO #2: The student will be able to identify and apply appropriate statistical analysis, to include techniques in data collection, review, critique, interpretation, and inference in the aviation and aerospace industry.

Data collected from the NASA ASRS database and the CASA Air Transportation Safety Board (ATSB) accident database will be interpreted, reviewed, and critiqued to infer statistical significance (=0.05) of a federally regulated commercial training requirement on the incidence of unsafe acts by remote pilots. Information gathered from the DOI SAFECOM database will also be collected and reviewed to compare the safety actions in a formalized UAS training program.

PO #3: The student will be able—across all subjects—to use the fundamentals of human factors in all aspects of the aviation and aerospace industry, including unsafe acts, attitudes, errors, human behavior, and human limitations as they relate to the aviator’s adaption to the aviation

environment toreach conclusions.

The research presented in this graduate capstone project (GCP) seeks to determine the influence of training on the change in human behavior and awareness of human limitations related to controlling automated systems that interact with a multimodal airspace system with the objective of reducing errors, unsafe acts, and attitudes committed by professional commercial remote pilots.

PO #4: The student will be able to develop and/or apply current aviation and industry-related research methods, including problem identification, hypothesis formulation, and interpretation of findings to present as solutions in the investigation of an aviation/aerospace-related topic.

Using the NASA ASRS database to plot the increase of reported UAS incidents in the U.S., this research will identify a problem that will be addressed through interpretation of the findings in other POs. The preliminary hypothesis is that requiring practical training in a UAS system leads to safer operations and a reduction in unsafe acts and errors. Analysis of the CASA-required RePL training and DOI UAS training program will be interpreted as findings to present as solutions.

PO #13: Unmanned Aerospace Systems. The student will investigate, compare, contrast, analyze and form conclusions to current aviation, aerospace, and industry- related topics in unmanned aircraft and spacecraft systems, including UAS systems, robotics and control, unmanned systems operations and payloads, and human factors in unmanned systems.

The research presented in this GCP will address the current topic of unmanned aircraft incursion into restricted or unauthorized airspace, causing a danger to the national air transportation system. UAS systems that utilize concepts in robotics and control such as autonomous navigation, teleoperation, and integration of payloads such as sense-and-avoid technology will be described as methods of improving the human factors aspect of situation awareness during UAS operation in complex airspace systems.

Project Introduction

Civil commercial UAS are a large area of growth in the U.S. national airspace system (NAS), and safety of operations is the primary goal of successful integration. As UAS become more integrated into a shared airspace system, avoiding airspace conflicts and near midair collisions (NMAC) becomes a priority. As the number of UAS operations grows, formal training is needed in safe operations and use of controlled airspace. As of February 1, 2018, there are 73,157 commercial RPC holders in the United States (Federal Aviation Administration [FAA], 2018a) and 1,371 waivers granted to RPC holders to operate within controlled airspace near airports (FAA, 2018b). The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Center of Excellence for UAS Research (COE) published a report in 2017 to determine the potential damage that would occur if a 1.2 kg (2.7 lb) quadcopter UAS impacted a commercial transport jet or a business jet and determined a UAS impact would cause more damage than a bird strike (Alliance for System Safety of UAS through Research Excellence, 2017). To date, one documented mid-air collision between a UAS and a manned aircraft has occurred within the U.S. NAS, when a recreational UAS pilot flew a small quadcopter UAS beyond visual line of sight (VLOS) and into the path of a military UH-60M helicopter (National Transportation Safety Board, 2017). Worldwide, five additional mid-air collisions between manned aircraft and UAS have occurred since 1997 with one of them resulting in fatalities (Australian Transport Safety Bureau [ATSB], 2017).

U.S. Commercial UAS Requirements

By law in the U.S., all civil aircraft operation requires a certificated pilot, a certified and registered aircraft, and operational approval; commercial UAS operation within the U.S. was originally authorized through Section 333 of the FAA Modernization and Reform Act (FMRA) of 2012which gave the FAA authority to determine if a UAS operation required an airworthiness certificate. UAS operators applied for waivers from existing regulations of certificated aircraft, and the commercial UAS industry could proceed within U.S. national airspace. As of September 2016, 5,551 individuals and organizations have received waivers to operate under Section 333 (FAA, 2016a). All of them still require a manned aircraft pilot certificate to operate UAS, as Section 333 of the FMRA did not provide the authority to waive the pilot certificate requirement.

Section 332 of the 2012 FMRA required the Secretary of Transportation to develop a plan to safely accelerate the integration of civil UAS into the NAS (FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012). A Notice of Proposed Rule Making (NPRM) was issued on February 23, 2015 that proposed regulations to address UAS operations, remote pilot certification, and aircraft registration. 4,708 comments to the NPRM were received (Operation and Certification of Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems, 2015). The final rule was released on June 28, 2016 as Title 14, Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) Part 107. The preamble to the final rule responded to the NPRM commenters in every topic. Required formal training was discussed, noting that many knowledge areas and skills required to fly a manned aircraft do not apply to UAS; specifically, “how to maintain visual line of sight of the unmanned aircraft or how to respond when signal to the unmanned aircraft is lost” (Operation and Certification of Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems, 2016a). Due to the VLOS containment of UAS under Part 107, the FAA took a risk-based approach to airman certificates for remote pilots and decided not to “propose specific training, flight experience, or demonstration of proficiency in order to be eligible for a certificate” (Operation and Certification of Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems, 2016a).

Australian Commercial UAS Requirements

Commercial UAS in Australia are regulated by CASA under Civil Aviation Safety Regulations (CASR) 1998, Volume 3 Part 101, Subpart 101.F (2017). As of September 2016, there were 5,780 commercial RePL holders in Australia (Civil Aviation Safety Authority [CASA], 2017b). Unmanned aircraft that weigh less than 2 kg may operate under an “excluded” category that includes notification prior to flight and operation within a strict list of standard operating conditions that mirror most of the same limitations of the FAA Part 107 regulations without requiring airman certification (CASA, 2017a). A summary of operating conditions and regulations that are common between FAA Part 107 and CASA Part 101 “excluded” category is located in Appendix A, Figure A1.

To operate unmanned aircraft over 2 kg or outside of the excluded category standard operating conditions, remote pilots must be authorized through a RePL which requires practical type training with a Remotely Piloted Aircraft System (RPAS) training provider. Specific required competency-based skills include navigating an RPAS, launching an RPAS, controlling an RPAS in normal and abnormal flight conditions, recovering an RPAS, and applying situational awareness in RPAS operations (Australian Government, 2016). In turn, RePL holders may only fly for authorized operators with a RPA operator’s certificate (ReOC). To operate with a ReOC, a safety case and comprehensive risk assessment must be completed for every operation that requires approval under Part 101. ReOCs are issued by RPA categories of multi-rotor, fixed-wing, and helicopter type aircraft across four different weight classes (CASA, 2018a). As of February 15, 2018, there are 1255 ReOC holders in Australia (CASA, 2018b).

Overview of NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System

ASRS is a database of voluntary reports by pilots, ATC, mechanics, and flight attendants of unsafe acts or behaviors that lead to a near-miss of an accident or an inadvertent violation of aviation regulations. To encourage participation, pilots who self-report near-misses or deviation from regulations or ATC instructions to the ASRS are assumed to have a “constructive attitude” and will tend to prevent future violations, so the FAA will not pursue enforcement action (FAA, 2011, p. 4). Given the voluntary nature of the ASRS, the reports are based on the interpretation of the individual. As a result, the sample of airmen represented in the ASRS database cannot be assumed to be part of a normally distributed population. However, the presence of incidents and violations does represent the presence of unsafe occurrences, and the ASRS data can be considered as a quantifiable lower bound of unreported occurrences (Connell, 2017).

Overview of DOI Safety Communique

The DOI Office of Aviation Services (OAS) provides aerial support for DOI agencies such as the National Park Service and the U.S. Geological Survey. OAS aircraft perform a multitude of operations including aerial fire suppression, wildlife surveys, search and rescue, and orthographic mapping. As such, the OAS maintains comprehensive operational procedures that apply to all use of UAS. All UAS operations fall under FAA Part 107, but the OAS also prescribes UAS aircraft airworthiness, preventative maintenance programs, safety hazard reporting, and a required initial UAS training course (A-450 Basic Remote Pilot) that includes an evaluation by a designated UAS Pilot Inspector (Bathrick, 2018).

The vision of the OAS is to “attain and sustain zero aircraft accidents across DOI” (Department of the Interior [DOI], 2018, para. 1). A practical aspect of this vision is the department-wide utilization of the DOI Safety Communique (SAFECOM) reporting system. Early studies by the DOI OAS indicated a correlation between reporting of all unsafe incidents, occurrences, and hazards, and the fleet-wide mishap rate. The SAFECOM database is also used to provide “kudos” to operators who react to unsafe situations in an exemplary manner (DOI, 2017a). The database is searchable without DOI credentials.

Review of Relevant Literature

Investigations of causal human factors in aviation incidents rely on a consistent and thorough taxonomy. A significant contribution to human factors research was made in 2000 by Shappell and Wiegmann, who assessed the utility of a standardized HFACS. The original HFACS was developed and tested by the U.S. military to aid aviation accident analysis, and the work of Shappell and Wiegmann sought to determine the suitability of the HFACS in the civilian commercial industry. Since the HFACS addresses human error at every level of the system, it enables companies and regulatory bodies to make interventions at the organizational level. Later studies by Kevin Williams of the FAA Civil Aerospace Medical Institute examined the suitability of the HFACS for analysis of UAS human factors mishaps.

UAS accident data was not available until the FAA began regulation of commercial UAS operations, so earlier research efforts relied on data from military UAS accidents. Williams (2004) analyzed data from the U.S. Army, Navy, and Air Force to classify accidents into categories that included human factors, maintenance, aircraft, and unknown. Of the human factors-related accidents, further categories were applied: alerts/alarms, display design, procedural error, skill-based error, or other. The data was classified by stated factors in the accident reports and the personal judgment of Williams. The difficulty with utilizing data across three branches of military flight operations was the vastly different philosophies of UAS operation, user interfaces, procedures, and aircrew training. The percentage of human factors-related accidents varied by aircraft type, between 21% and 68% (Williams, 2004). However, Williams’ study did not utilize a formal HFACS.

The framework of the HFACS developed by Wiegmann & Shappell and adopted by the Department of Defense primarily existed to determine latent failures in organizational influences, unsafe supervision, and unsafe preconditions that would create an environment predisposed to human error, specifically, unsafe acts. Tvaryanas, Thompson, and Constable (2005) reviewed six prior studies of UAS human factors and discovered the lack of a common classification framework between the studies, with the exception of one study that utilized the Wiegmann & Shappell HFACS, but only analyzed U.S. Army UAS data (Manning, Rash, LeDuc, Noback, & McKeon, 2004). Tvaryanas et al. then reviewed ten years of UAS accident data, coding the human factors-related accidents using the Department of Defense (DoD) HFACS (version 5.7). Again, causes for unsafe acts were found to vary widely between branches of the military. Skill-based errors were more common in Air Force mishaps, while procedural violations were more common in Army operations. The overall conclusion showed that latent failures at the organizational, supervisory, and preconditions for operation contributed to more than half of UAS mishaps as analyzed (Thompson, Tvaryanas, & Constable, 2005). The results of this study further validate the use of the HFACS for UAS incident analysis.

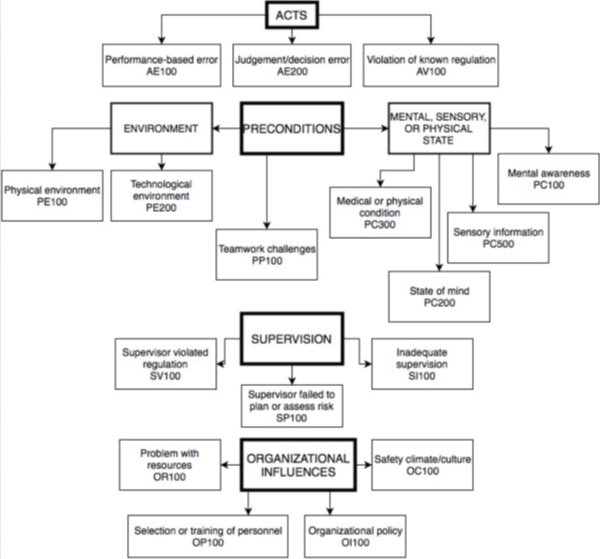

Classification systems used to make safety assessments need to be updated on a regular basis to ensure validity and efficacy of the ratings. DoD HFACS version 7.0 was developed and validated in 2015 by King, Strongin, Lawson, and Kuhlmann of the Air Force Research Laboratory, 711th Human Performance Wing. The objective of the HFACS update was to improve inter-rater reliability which conserving compatibility with existing databases. The HFACS prior to 2013 contained 149 rating codes, several of which were rarely or never used. HFACS rating codes were condensed and re-written, and a stepwise checklist was developed to systematically guide investigators and researchers through the consideration of “nanocodes” (King, Strongin, Lawson, & Kuhlmann, 2015). The re-worked HFACS was validated through several test iterations of the newly formed checklist. The final conclusion acknowledged that an “optimally reliable” human factors taxonomy was still yet to be realized, but the development of a guiding checklist provides a reliable framework to use a common HFACS in rating different databases. A flowchart adapted from the HFACS v. 7.0 checklist is located in Appendix A, Figure A2.

The validity of a reporting system is only confirmed if the data is accurate. Data from self-reported databases can only be considered as a lower bound of known incidents, in part because unsafe acts may go unreported if the outcome is innocuous. Gilbey, Tani, and Tsui (2016) performed two qualitative studies to measure the likelihood of reporting unsafe acts. The first study measured participant’s responses to descriptions of unsafe acts; bad outcomes were much more likely to be reported. In the second study, prompts were given to influence the likelihood of reporting unsafe acts, and evidence was shown that explicit prompts increased the likelihood of reporting unsafe acts with innocuous outcomes. This study highlights the difference between the implicit nature of option ASRS reports and the explicit reporting requirement of the SAFECOM database.

A significant number of reported near mid-air collisions have been voluntarily reported to the ASRS by UAS crewmembers, ATC, and manned aircrew. Sharma (2016) analyzed UAS incidents in the NAS using descriptive statistics, determining the frequency of reports containing accounts of airspace violations and NMAC by UAS in the NAS. Data were obtained from the NASA ASRS, the FAA Aviation Safety Information Analysis and Sharing (ASIAS) system, FAA NMAC system, and FAA-released UAS Sightings Reports. An upward trend in overall UAS-related reporting was noted. Class B airspace was the location of most UAS-related events, with California and New York being the highest-reported regions for UAS incidents (Sharma, 2016). Several UAS management technologies were offered as recommendations for reducing the number of safety incidents. Management techniques included geo-fencing, real-time flight planning applications, a proposed UAS Traffic Management (UTM) system, and ground-based sense and avoid (GBSAA) systems such as TIS-B and ADS-B (Sharma, 2016). Recommendations for performance- or risk-based standards were outside the scope of the research. The data was categorized by all UAS events, not specific to unsafe acts by pilots. While providing a valuable summary of UAS incidents and potential technological solutions, the data is still open to analysis of specific occurrence categories to further determine if technology would positively impact safety or if a more holistic approach is necessary.

A characteristic of modern commercial UAS is the highly-automated nature of the navigation system. Teleoperation provides the least amount of automation, but sensors and controllers provide autonomous navigation capability for a greater level of precision. However, taking a passive human-on-the-loop approach to control has human factors implications in the ability to efficiently detect and react to system failures, as studied by Molloy and Parasuraman in the 1996 edition of Human Factors. Three groups were tasked with performing complex flight simulation tasks that included tracking aircraft location, managing fuel load, and monitoring engine status. The summary of the study showed that “automation-related monitoring inefficiency occurs even when there is a single automation failure” (Molloy & Parasuraman, 1996, p. 311). The poorest performance in automation monitoring occurred when the participants were simultaneously engaged with a manual task. The research also was the first to empirically highlight a “vigilance decrement” for automation monitoring, where vigilance was lower in the final ten minutes of the simulator flights than in the first ten minutes (Molloy & Parasuraman, 1996). However, the research was performed with participants that did not have prior experience with the tested automation tasks, leading to a recommendation for replicating the research with trained or experienced pilots. Although the research was not followed up in this regard, the acknowledgment of an impact on vigilance through experience and training provides a compelling area of research in UAS training.

In 2002, the U.S. Air Force studied the impact of flight experience on the speed and accuracy of pilots to learn to fly the RQ-1A Predator UAV (Schreiber, Lyon, & Martin, 2002). Seven groups of military and civilian pilots were trained to fly the RQ-1A with experience including qualified RQ-1A pilots, T-38 pilots, civilian pilots with single-engine instrument experience, and non-pilots. The results showed that civilian pilots with recent experience scored nearly as well as military T-38 pilots with recent experience on performance. The results showed that 150-200 hours of previous flying experience was sufficient to prepare a pilot for RQ-1A training (Schreiber et al., 2002).

The FAA utilized a risk-based approach to developing Part 107 regulations. Baldwin and Black (2008) in the journal Law and Policy advocated a responsive risk-based regulatory environment. A risk-based approach to regulation uses an “evidence-based means” to prioritize resources and attention to the highest potential risks. Prioritizing resources permits regulators to respond to issues with time and resources than would be required to respond to all issues. Baldwin and Black (2008) developed a framework to advise regulators with methods of responsive risk analysis. The elements that regulators should be responsive to include the regulated firms’ behavior, attitude, and culture; the institutional environment; regulatory performance; and change (Baldwin & Black, 2008). Using this framework sheds light on the efficacy of the FAA’s analysis in developing Part 107 regulations that did not include a practical training element.

A slightly different approach to measuring the effectiveness of human monitoring of automation was used by Williams (2012), who examined the effect of sensory input on pilot reaction to UAS system failures. Aspects of the study also examined pilot experience and the level of automation. The greatest effect was gained from the presence of sound in reacting to engine failures. Contrasting Molloy & Parasuraman (1998), higher levels of automation did not lead to vigilance decrements (complacency). Additionally, pilots performed better than non-pilots during simulated manual control conditions, suggesting that previous flight experience makes a difference, although Williams stopped short of concluding the differences were due to aircraft training and flight experience. Although the results did not conclusively suggest a significant impact of practical training in UAS operations, it does highlight the need for further research in this area.

Situation awareness and the lack thereof is a large component of the commercial UAS incidents from the NASA ASRS database. Situation awareness (SA) was defined by Endsley (1988) as the perception of elements of the operating environment, the comprehension of their meaning, and the projection of their status in the near future. However, Drury, Riek, and Rackliffe (2006) suggest that Endsley’s widely-accepted definition of SA assumes that the human is the only intelligent part of the system. In control of robotic systems such as UAS, the robots need information about the environment as well as operating instructions. The human operator is just one of the many parts of the UAS and is not the primary source of sensory data. Drury, Riek, and Rackliffe (2006) studied the UAS-related SA for the three roles that also appear in NASA ASRS reports: UAS operators, ATC, and pilots of manned aircraft. The ASRS reports often cite only a “lack of SA” without defining the types of awareness that need to be aided for better operational safety. Through their observations, the researchers developed recommendations for better human-UAS interfaces to increase the fidelity of UAS SA. This research was important because it suggests spatial awareness is more an issue of human-machine interface than it is for training.

Methodology

To determine if a monotonic relationship exists between the ASRS, ATSB, and SAFECOM databases, they require classification with a common taxonomy. The DoD HFACS v. 7.0 checklist (King et al., 2015) and adapted flowchart located in Appendix A, Figure A2, was used to process the reports in each of the databases and determine the contributory human factors that may have influenced the actions of the operator. 17 codes are used to categorize human factors events by operator acts, preconditions, supervision, and organizational influences, with each code containing specific nanocodes for further classification. A summary table of the coded databases is located in Appendix B, Table B1. An a priori power test of the bivariate correlation performed using G*Power (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2009b) showed that total sample size could remain below 19 for a strong positive correlation (rs > 0.5), so nanocodes were not used to further process the data.

ASRS Analysis

Although the ASRS data is self-reported, it is de-identified and analyzed by NASA to allow the database to be searchable by event type and operator type. As of February 10, 2018, 100 ASRS results appeared in a search of the database with aircraft type filtered by “UAS” (National Aeronautics & Space Administration, 2018). To process the database for comparison with the civil ATSB database, the data set was downloaded in Microsoft Excel spreadsheet format and further filtered. Data from reports concerning military UAS were excluded. Reports by observers that were not part of the UAS operation were not included because human factors could not be reliably determined from a third-person narrative. Reports containing irrelevant data such as personal disagreement with current regulations were also rejected. The resulting reports provided a sample set of 30 civil UAS incidents that included a combination of unsafe acts, errors, mishaps, and lost link events. The user narratives and NASA synopses of causal factors were coded with the HFACS v. 7.0 checklist to categorize each reported event for statistical analysis. A summary of coded ASRS reports can be found in Appendix B, Table B1.

ATSB Analysis

Civil aviation mishap investigations in Australia are performed by the ATSB. Results are published in a summary database that can be filtered by operation type, occurrence class, aircraft model, and more (ATSB, 2018). To obtain reports of UAS mishaps and incidents, the database was filtered by the sector “remotely piloted aircraft.” 119 records were obtained and exported into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for analysis. The ATSB summary of each event was the only narrative available for processing, which provided a constrained list of seven incidents that were analyzed to include human factors. The HFACS v. 7.0 checklist was used to code each record for statistical analysis. A summary of coded ATSB reports can be found in Appendix B, Table B1.

SAFECOM Analysis

The SAFECOM database meets the requirements set forth by the DOI and U.S. Forest Service to report safety incidents and aircraft mishaps in order to meet the zero-mishap benchmark. A standardized form (OAS-34) is used to report any condition, observation, act, maintenance issue, or circumstance with personnel or aircraft that may potentially cause a mishap (DOI, n.d.a). The OAS-34 form categorizes SAFECOM reports automatically via user input. Users may submit a narrative of events and a synopsis of corrective actions that should be taken.

The 3D Robotics (3DR) Solo multirotor aircraft is utilized by multiple agencies within the DOI and is used in the interagency A-450 Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems (sUAS) Basic Remote Pilot Course (DOI, n.d.b). SAFECOM reports filtered into aircraft type (UAS) and aircraft model containing any variation of the term “solo” provided 34 reports, which were exported into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for analysis. Of these, ten reports contained no narrative or categorical data or were unrelated to human factors. The remaining 24 were coded with the HFACS v. 7.0 checklist. One report (SAFECOM Event No. 17-0592) contained no narrative but categorized the report with a pilot action hazard and damage to the avionics and propellers of the aircraft. This sample was coded as a judgment or decision-making error, which includes instances of “an honest mistake” (King et al., 2015, p. 21). SAFECOM summary data is located in Appendix B, Table B1.

Hypothesis

The research presented in this graduate capstone project seeks to determine if political bodies with operational regulations that require formal training appear to correlate with other political bodies. The null hypothesis for this research states there is no significant correlation ( = 0.05) between ASRS, ATSB, and SAFECOM data that has been analyzed by the DoD HFACS v. 7.0 process. The alternate hypothesis is that a strong positive correlation will exist between the HFACS coded analysis of the databases from organizations that require formal training.

Since these databases contain ordinal variables and are not assumed to be normally distributed, the nonparametric Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rs)was calculated with StatCrunch online data analysis software (Pearson Education, Inc., 2017) to obtain a strength of monotonic relationship between ASRS, ATSB, and SAFECOM reports (Lund Research Ltd., 2013).

To reject the null hypothesis and obtain a positive correlation coefficient rs > 0.30, = 0.05, with 80% (0.8) effect size, a power analysis was performed in G*Power (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2009a) a priori, showing a total sample size of 19 is required. Comparing ASRS, ATSB, and SAFECOM database results against each other provides at least 31 samples in every instance.

Limitations

Since the three analyzed databases differ in reporting purposes and methodology, the comparison is limited to the HFACS v. 7.0 categories as coded. Prior studies (Shappell & Wiegmann, 2000; Thompson, Tvaryanas, and Constable, 2005; King, Strongin, Lawson, and Kuhlmann 2015) utilized multiple working groups to verify inter-rater reliability in their reviews of the HFACS. Working groups are outside the scope of this research, so the reliability of the categorization rests on the expertise and judgment of the author. Williams (2004) also presented a review and analysis of UAS accident data without the aid of working groups, as the “classification was based on stated causal factors in the reports, the opinion of safety center personnel, and personal judgment of the author” (Abstract, p. i.).

The ASRS and SAFECOM databases are voluntary and used for safety statistics-gathering only, while the ATSB database is the result of government investigations, so the objectives of each database do not share a common theme. Additionally, because the data analyzed for this research is primarily self-reported, causal factors could not reliably be determined without expert analysis of additional information for each report.

Results

Using the data from Appendix B, Table B1 to compare the percentages of HFACS coded incident factors, StatCrunch (Pearson Education, Inc., 2017) was used to calculate Spearman’s coefficient between all three databases. Comparing the ASRS and ATSB HFACS codes provides rs = 0.47 (p-value 0.0639), indicating a positive monotonic relationship (Lund Research Ltd., 2013). Comparing the ASRS and SAFECOM provided similar results with rs = 0.46 (p-value 0.0749). However, the ATSB and SAFECOM HFACS analysis provided a much higher monotonic relationship, with rs = 0.69 (p-value 0.003). The null hypothesis cannot be rejected for comparison of the ATSB and SAFECOM HFACS codes with ASRS codes, but in comparing the ATSB HFACS codes with the SAFECOM HFACS codes, the null hypothesis can be rejected in favor of the alternate hypothesis.

Analysis

Although a positive correlation exists between the HFACS coding of ASRS, ATSB, and SAFECOM data, analysis of individual data points is needed to explain outliers and provide recommendations for relevant improvement.

HFACS Means

Analysis of combined HFACS data from ASRS, ATSB, and SAFECOM databases indicated valuable total results. As depicted in Appendix B, Table B1, the means of HFACS codes with the total highest occurrences are AE200 (judgment and decision-making errors) appearing in 85.24% of all reports, followed by SP100 (failure to appropriately plan and assess risk) appearing in 73.57% of all reports, OP100 (personnel selection and training) appearing in 53.49% of reports, and PE200 (automation and workspace design) which appears in 46.19% of reports across the studied datasets.

Outliers

Outliers may influence exact linear correlation calculations to the extent that a correlation value may not be categorized correctly according to strength (Mukaka, 2012). Use of Spearman’s correlation coefficient allows outliers and non-normal distributions, but their presence still provides valuable insight for analysis.

The HFACS analysis code AV100 (violation of known regulations, mean = 33.65%, SD = 46.46%) appeared in 86.67% of ASRS reports, compared with 14.29% of ATSB reports and 0% of SAFECOM reports. This is potentially due to the reporting nature of the ASRS; pilots are incentivized to report unsafe acts to prevent enforcement action following a violation of regulations (FAA, 2011). OI100 (organizational policy issues, mean = 22.26%, SD = 15.39%) also appeared much more often under ASRS reports than in ATSB and SAFECOM reports. ASRS reports that were coded with OI100 involved remote pilots who conducted a flight that violated a Part 107 rule, where an organizational risk assessment policy would have prevented the flight from occurring under the conditions that led to the violation.

Organizational resource problems (OR100, mean = 15.83%, SD = 14.02%) did not appear in ATSB reports. This is likely due to the regulatory separation of the RePL and ReOC in CASA 101; ReOC contributing factors may not be included in ATSB mishap reports. PC100 at 57.14% (mental awareness, mean = 32.10%, SD = 22.81%) and PC500 at 42.86% (sensory information, mean = 22.90%, SD = 17.29%) appeared most in coding of the ATSB data. Since the ATSB reports only contain investigative narratives, this is likely due to the format used to categorize and publish ATSB incident reports.

The primary outlier in the SAFECOM HFACS codes was PE200 (technological environment) appearing in 66.67% of reports (mean = 46.19%, SD = 19.21%). 71% (17) of the HFACS-coded DOI report narratives included an equipment anomaly that precluded the pilot action. 54% (13) of the SAFECOM reports included equipment anomalies that led to aircraft damage, with broken propellers being the leading category of damage. Unexpected poor battery performance and GPS or compass anomalies accounted for all of the reported equipment failures leading to safety incidents. SAFECOM reports with GPS or compass failures reported either known local magnetic anomalies or post-incident notification of DoD GPS jamming tests in the surrounding areas, which indicates a heightened environmental risk for the 3DR Solo aircraft as utilized in the various missions of DOI agencies, which include search and rescue, wildlife surveys, and wildland fire impact assessments in remote locations (DOI, 2016).

HFACS v. 7.0 code OP100 – Selection or Training of Personnel

OP100 was identified as a contributing factor in a mean of 53.49% of incidents across all three databases. The contributing factor rate was highest in ASRS incidents (70%), the next highest was in ATSB reports at 57.14%, and the lowest rate appeared in 33.33% of SAFECOM reports. Where the mean-SD = 38.54%, the SAFECOM OP100 rate is the only HFACS code outlier that appears below one standard deviation from the mean in the entire matrix of compiled data.

Conclusion

The higher positive correlation to confirm the alternative hypothesis between human factors incidents reported in ASTB and SAFECOM databases suggests a similarity in organizational policy. The low outlier in SAFECOM selection and training of personnel suggests that the DOI UAS training course is a successful method of reducing human factors-related mishaps.

Recommendations

Responsive Regulations

Baldwin and Black (2008) recommend that regulators take a responsive approach to risk-based regulations by being attentive and responsive to the behavior, attitudes, and cultures of regulated actors, as well as changes to these characteristics. Tracking change in behavior, attitudes, and culture across the regulatory environment provides the regulator with a measure of their capacity to influence or regulate behavior (Oliver, 1991). A position paper (Wallace, 2016) in the International Journal of Aviation, Aeronautics, and Aerospace suggests adapting the WINGS Pilot Proficiency Program as a method of Remote Pilot recertification instead of re-taking the Remote Pilot certification exam per 14 CFR Part 107.73 (Operation and Certification of Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems, 2016b). The primary argument is that the current approach of requiring a written recertification test in the same knowledge areas as the original certification exam “potentially squanders the opportunity to engage remote pilots within the larger aviation community and foster the development of a shared safety culture” (Wallace, 2016, p. 1-2). A positive safety culture, according to the FAA, includes “shared values, actions, and behaviors that demonstrate a commitment to safety… and personnel continue to learn and develop through training and coaching” (FAA, 2016c, p. 11). A set of “shared values” in a safety culture of Remote Pilots may not have the opportunity to organically develop without the presence of manned pilots and without progression through formal, standardized training programs that encourage hazard reporting (such as ASRS) and responsible organizational risk assessment such as found in the Australian ReOC requirements.

Changing the requirements of 14 CFR Part 107.73 would require the FAA to pursue another lengthy NPRM process to create an update to the regulation. Using the DOI A-450 sUAS syllabus and training outline as a template for successfully reducing human factors mishaps, an alternative action could be to release an advisory circular that provides guidance on organizational risk assessment and formal training program for commercial operations. Doing so would provide Remote Pilots with a clear path to developing their own safety culture and holding themselves to the same “zero mishap” vision of the DOI OAS. Unmanned aircraft crew training and certification is one of the many research focus areas chartered by the FAA-designated UAS Center of Excellence; research and industry input could be used in the formation of this research-based advisory circular dissemination (FAA, 2016b).

Technology

Most (86.67%) of analyzed ASRS reports involved violation of known regulations, most often through unintentional airspace incursion. Aircraft make and model were not present in the UAS reports, but the narratives did not provide evidence that technology succeeded in providing a positive effect on situation awareness. Dà-Jiāng Innovations Science and Technology Company (DJI) has provided advisory airspace restrictions by geo-fencing operations in or near no-fly-zones through their “GEO” flight planning system (DJI, 2018). The feature was unveiled in 2014, but gained national attention in January 2015, when an individual unintentionally flew a recreational DJI Phantom 2 quadcopter onto the grounds of the White House in Washington, DC (Schmidt & Shear, 2015). Media images clearly depict the prominent manufacturer logo on the top of the aircraft, which led to tightened geo-restrictions via an aircraft firmware update one day after the incident (Fingas, 2015). However, management of data such as flights near restricted or sensitive locations that require geo-fencing will be an issue occurring much more frequently. An August 2017 memo from the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Los Angeles office warns with moderate confidence that “Chinese-based company DJI Science and Technology is providing U.S. critical infrastructure and law enforcement data to the Chinese government” (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2017, para. 2). The DOI justification for selecting the 3DR Solo quadcopter for training and remote sensing was the presence of a “secure digital data frequency with AES encryption” (p. 2, para. 2) and “the ability to decline automated file sharing” (p. 3, para. 9) (DOI, 2017b). Commercial users of UAS should be aware of the security of the data collected during flight, including recorded video, images, and geo-referenced flight logs.

UAS Traffic Management System

Section 2208 of the FAA Extension, Safety, and Security Act of 2016 directs the FAA to establish a pilot program for “airspace hazard mitigation” to reduce threats from “hostile or errant” UAS. The development of the NASA UTM system supports the requirement of Section 2206. The planned UTM technology will primarily support beyond-line of sight (BLOS) operations at low altitudes (<400’ AGL) but will also rely on data sharing between operators and the FAA via application programming interfaces (API) (Kopardekar & Bradford, 2017). Successful implementation of a UTM will apply to civil commercial operations and will likely require a widespread education effort to implement successfully.

Industry-Led Training Standards

Several industry groups are recognizing the gap in appropriate training and are beginning to move towards formal training, developing frameworks for safe operations that promulgate through membership and advocacy groups such as the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI). AUVSI chartered the development of a Trusted Operator Program (TOP) in January 2018 that includes industry stakeholders and seeks to “unify and reach consensus on minimum levels of training protocols that support RELIABILITY, SAFETY, PROFESSIONALISM and TRUST” (AUVSI, n.d., para. 1). As of January 12, 2018, a TOP steering committee has been named and a final draft of American National Standards Institute-accredited training standards is due for review from April 20-25, 2018. TOP certificates will be granted to qualified pilots, with recurring training required every 24 months (T. Lamb, email to author, January 19, 2018). Certificate programs have precedence in other industries such as non-destructive testing, computer network communications, and project management (American Society for Nondestructive Testing 2017; Cisco, n.d.; Project Management Institute, Inc., 2018). A UAS Flight Safety Endorsement is offered by Unmanned Safety Institute, a partner company of ARGUS International, an aircraft charter safety consulting and certification company. The Flight Safety Endorsement provides Part 107 Remote Pilots with a safety certificate that can be applied to insurance discounts for safe operations (Unmanned Safety Institute, 2017).

A more inclusive method is the development and publication of industry and operator codes of conduct that communicate guidelines for professionalism and operational safety. The most recent example is the UAS Pilots Code (UASPC) developed by the Aviator’s Code Initiative and the University Aviation Association. The UASPC contains seven focus areas that include UAS pilot responsibilities, training and proficiency, security and privacy, environmental issues, and use of technology (Baum, Kiernan, Steinman, and Wallace, 2018). While not considered a replacement for federal aviation regulations, the UASPC provides guidance for remote pilots who do not originate from the formal training background of manned aviation by providing optional guidance beyond the FAA’s AC 107-2.

Summary

In this research of human factors-related UAS incidents, three mishap and incident reporting databases were analyzed to determine contributing human factors. A statistically significant correlation ( = 0.003) was found between Australia’s ATSB reports and the UAS reports in the DOI SAFECOM reporting system, indicating a similarity in operational guidelines. The NASA ASRS database organized by human factors codes did not show a correlation with the other databases. The risk-based approach used by the FAA to develop UAS regulations provides an open and accessible airspace system that requires responsible and knowledgeable users. The recommendation for safe integration of UAS into the NAS is for industry-led groups to develop formal training standards for commercial operators, including robust reporting requirements to encourage safety culture and track successful impact to a reduction of human errors and unsafe acts due to lack of training.

References

Alliance for System Safety of UAS through Research Excellence. (2017). Volume II – UAS airborne collision severity evaluation – quadcopter final report. Retrieved from www.assureuas.org/projects/deliverables/a3/Volume%20II%20-%20UAS%20Airborne%20Collision%20Severity%20Evaluation%20-%20Quadcopter.pdf

American Society for Nondestructive Testing. (2017). Certification. Retrieved from https://www.asnt.org/MajorSiteSections/Certification

Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International. (n.d.). AUVSI remote pilots council. Retrieved from www.auvsi.org/rpc-top

Australian Government. (2016, March). AVI30316, Certificate III in aviation (remote pilot – visual line of sight) (release 1). Retrieved from https://training.gov.au/Training/Details/AVI30316

Australian Transport Safety Bureau. (2017). A safety analysis of remotely piloted aircraft systems (2nd ed.) (ATSB Transport Safety Report AR-2017-016a). Retrieved from https://www.atsb.gov.au/media/5773362/ar-2017-016a_final.pdf

Australian Transport Safety Bureau. (2018). Aviation safety investigations & reports [Database]. Retrieved from https://www.atsb.gov.au/publications/safety-investigation-reports/?mode=Aviation

Baldwin, R., & Black, J. (2008). Really Responsive Regulation. The Modern Law Review, 71(1), 59–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2230.2008.00681.x

Bathrick, M. (2018, January 1). DOI use of unmanned aircraft systems (UAS). [Memorandum]. Retrieved from https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/opm-11.pdf

Baum, M.S., Kiernan, K.K., Steinman, D.W., & Wallace, R.J. (2018, January). In D. Arendt et al. (Ed.), UAS pilots code, condensed version. Retrieved from www.secureav.com/UASPC-condensed-v1.0.pdf

Cisco. (n.d.). Training & certifications. Retrieved from https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/training-events/training-certifications/certifications.html

Civil Aviation Safety Authority. (2017a, February). Advisory Circular 101-10, Remotely piloted aircraft systems – operation of excluded RPA (other than model aircraft). Retrieved from https://www.casa.gov.au/files/ac10110pdf

Civil Aviation Safety Authority. (2017b, December). Drone safety review. Retrieved from https://www.casa.gov.au/aircraft/standard-page/drone-safety-review

Civil Aviation Safety Authority. (2018a, February). Getting licensed and certified to fly a drone. Retrieved from https://www.casa.gov.au/aircraft/standard-page/commercial-unmanned-flight-gaining-your-remotely-piloted-aircraft-pilot

Civil Aviation Safety Authority. (2018b, February). UAS certificate holders [Database]. Retrieved from https://www.casa.gov.au/aircraft/standard-page/uas-certificate-holders

Civil Aviation Safety Regulations 1998, Volume 3 Part 101, Subpart 101.F (2017).

Connell, L.J. (2017). Unmanned aerial vehicle reports [Data set]. Retrieved from https://asrs.arc.nasa.gov/docs/rpsts/uav.pdf

Dà-Jiāng Innovations Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (2018). GEO zone map. Retrieved from https://www.dji.com/flysafe/geo-map

Department of the Interior. (2016, May 27). Demonstrated unmanned aircraft system (UAS) mission applications. Retrieved from https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/doi_uas_mission_applications_v4.0.pdf

Department of the Interior. (2017a, May 18). Safecom presentation [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3whGZbAhllY

Department of the Interior. (2017b, July 11). Solicitation No. D17PS00629, Brand name justification. Washington, D.C.: Interior Business Center. Retrieved from https://www.fbo.gov/utils/view?id=0dc4919d022b2c9517312c68f54ca146

Department of the Interior. (2018). OAS mission statement. Retrieved from https://www.doi.gov/aviation/mission

Department of the Interior. (n.d.a). Aviation safety communique (SAFECOM) [Database]. Retrieved from https://www.safecom.gov

Department of the Interior. (n.d.b). DOI UAS fleet. Retrieved from https://www.doi.gov/aviation/uas/fleet

Drury J.L., Riek L., & Rackliffe N. (2006). A Decomposition of UAV-Related Situation Awareness. Proceedings of the 1st ACM SIGCHI/SIGART Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 88–94. https://doi.org/http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/1121241.1121258

Endsley, M.R. (1988). Design and evaluation for situation awareness enhancement. Proceedings of the Human Factors Society 32nd Annual Meeting. Santa Monica, CA: Human Factors Society.

FAA Extension, Safety, and Security Act of 2016, Pub. L. No. 114-190 § 2206, 130 Stat. 630 (2016). Retrieved from https://www.faa.gov/uas/resources/uas_regulations_policy/media/Pages-from-PLAW-114publ190.pdf

FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012, 49 U.S.C. § 40101 (2012).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009a). G*Power (Version 3.1.9.3) [Computer software]. Kiel, Germany: Universität Kiel.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009b). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149-1160.

Federal Aviation Administration. (2011). Advisory Circular 00-46E, Aviation safety reporting program. Retrieved from https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/ Advisory_Circular/AC%2000-46E.pdf

Federal Aviation Administration. (2016a). Authorizations granted via section 333 exemptions [Database]. Retrieved from https://www.faa.gov/uas/ beyond_the_basics/section_333/333_authorizations/

Federal Aviation Administration. (2016b). FAAs Center of Excellence for unammed aircraft systems alliance for system safety of UAS through research excellence. Retrieved from https://www.faa.gov/uas/research/media/UAS-Assure-COE.pdf

Federal Aviation Administration. (2016c). Safety management system [National Policy Order 8000.369B]. Retrieved from http://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Order/FAA_Order_8000.369B.pdf

Federal Aviation Administration. (2018a). Airmen certification system active pilots summary, (02/01/2018. [Data set]. Retrieved from http://registry.faa.gov/activeairmen/ M70_Active_Pilots_Summary.pdf

Federal Aviation Administration. (2018b). Part 107 waivers granted [Database]. Retrieved from https://www.faa.gov/uas/request_waiver/waivers_granted/

Fingas, J. (2015, January 28). DJI no longer lets you fly its drones in Washington, DC. engadget. Retrieved from https://www.engadget.com/2015/01/28/dji-drone-update-bars-washington-flights/

Gilbey, A., Tani, K., & Tsui, W. H. K. (2016). Outcome Knowledge and Under-reporting of Safety Concerns in Aviation. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 30(2), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3179

King, R. E., Strongin, T., Lawson, J., & Kuhlmann, E. W. (2015). The Development and Inter-Rater Reliability of the Department of Defense Human Factors Analysis and Classification System, Version 7.0 (AFRL-SA-WP-TR-2015-0009). Retrieved from www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a623729.pdf

Kopardekar, P., & Bradford, S. (2017, January 31). UAS traffic management (UTM) research transition team (RTT) plan. Moffett Field, CA: NASA Ames Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.faa.gov/uas/research/utm/media/FAA_NASA_UAS_Traffic_Management_Research_Plan.pdf

Lund Research Ltd. (2013). Spearman’s rank-order correlation. Retrieved from https://statistics.laerd.com/statistical-guides/spearmans-rank-order-correlation-statistical-guide.php

Manning, S. D., Rash, C. E., LeDuc, P. A., Noback, R. K., & McKeon, J. (2004). The Role of Human Causal Factors in U.S. Army Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Accidents (USAARL Report No. 2004-11). Retrieved from www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a421592.pdf

Molloy, R., & Parasuraman, R. (1996). Monitoring an Automated System for a Single Failure: Vigilance and Task Complexity Effects. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 38(2), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872089606380211

Mukaka, M. (2012). A guide to appropriate use of Correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Medical Journal: The Journal of Medical Association of Malawi, 24(3), 69–71. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3576830/#R4

National Aeronautics and Space Administration. (2018). Aviation safety reporting system [Database]. Retrieved from https://asrs.arc.nasa.gov/search/database.html

National Transportation Safety Board. (2017). Inflight collision of UAS and helicopter (NTSB Incident Report DCA17IA202A). Retrieved from https://app.ntsb.gov/pdfgenerator/ ReportGeneratorFile.ashx?EventID=20170922X54600&AKey=1&RType=HTML&IType=IA

Oliver, C. (1991). Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 145-179. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy. libproxy.db.erau.edu/stable/258610

Operation and Certification of Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems; a Proposed Rule by the Federal Aviation Administration, 80 Fed. Reg. 9,543 (February 23, 2015) (to be codified at 14 C.F.R. pts. 101, 107, 183, 21, 43, 45, 47, 61, 91). Retrieved from https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2015/02/23/2015-03544/operation-and-certification-of-small-unmanned-aircraft-systems

Operation and Certification of Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems, 81 Fed. Reg. 42,063 (proposed June 28, 2016a) (to be codified at 14 C.F.R. pt. 107). Retrieved from https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/06/28/2016-15079/operation-and-certification-of-small-unmanned-aircraft-systems

Operation and Certification of Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems, 14 C.F.R. § 107 (2016b). Retrieved from https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=e331c2fe611df1717386d29eee38b000&mc=true&node=pt14.2.107&rgn=div5

Pearson Education, Inc. (2017). StatCrunch [Computer software]. Retrieved from https://www.statcrunch.com

Project Management Institute, Inc. (2018). Project management professional (PMP). Retrieved from https://www.pmi.org/certifications/types/project-management-pmp

SAFECOM Event No. 17-0592 [Web-based incident report]. (2017, July 18). Retrieved from https://www.safecom.gov/searchone.asp?ID=21777

Schmidt, M.M. & Shear, M.D. (2015, January 25). A drone, too small for radar to detect, rattles White House. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/27/us/white-house-drone.html?hp&action=click&pgtype=Homepage&module=second-column-region®ion=top-news&WT.nav=top-news&assetType=nyt_now&_r=0

Schreiber, B. T., Lyon, D. R., & Martin, E. L. (2002). United States Air Force Impact of Prior Flight Experience on. Mesa, AZ.

Shappell, S.A., & Wiegmann, D.A. (2000). The human factors analysis and classification system – HFACS (DOT/FAA/AM-00/7). Retrieved from https://www.nifc.gov/fireInfo/fireInfo_documents/humanfactors_classAnly.pdf

Sharma, R. S. (2016). Investigation into Unmanned Aircraft System Incidents in the National Airspace System. International Journal of Aviation, Aeronautics, and Aerospace, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.15394/ijaaa.2016.1146

Thompson, W. T., Tvaryanas, A. P., & Constable, S. H. (2005). U.S. Military Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Mishaps: Assessment of the Role of Human Factors Using Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS) (HSW-PE-BR-TR-2005-0001). Retrieved from www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a435063.pdf

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. (2017, August 9). Da Jiang Innovations (DJI) likely providing U.S. critical infrastructure and law enforcement data to Chinese government. [Memorandum]. Los Angeles, CA: Homeland Security Investigations. Retrieved from https://info.publicintelligence.net/ICE-DJI-China.pdf

Unmanned Safety Institute. (2017). UAS flight safety endorsement. Retrieved from https://www.unmannedsafetyinstitute.org/product/flight-safety/#tab-description

Wallace, R. J. (2016). Position Paper: Safety Culture: Why the FAA Should Consider Adapting the WINGS Pilot Proficiency Program as a Method of Remote Pilot Recertification. International Journal of Aviation, Aeronautics, and Aerospace, 3(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.15394/ijaaa.2016.1138

Williams, K. W. (2004). A Summary of Unmanned Aircraft Accident / Incident Data: Human Factors Implications (DOT/FAA/AM-04/24). Retrieved from www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a460102.pdf

Appendix A

Figures

| Limitation | FAA Part 107 | CASA Part 101 |

| Maximum weight

Maximum altitude |

Less than 55 lbs. (24.94 kg)

400 feet above ground level |

2 kg

120 meters (400 feet) AGL |

| Maximum distance | Within visual line of sight* | Within VLOS |

| Operation over people | Not permitted* | > 30 meters (100 feet) |

| Time of day | Daytime only* | Daytime only |

| Pilot certificate | Remote Pilot Certificate | None |

Figure A1. Comparison of FAA Part 107 and CASA Part 101 (excluded category) risk-based operational limitations. Adapted from Federal Aviation Administration, 2017, Getting started with your UAS, retrieved from https://www.faa.gov/uas/getting_started/ and Civil Aviation Safety Authority, 2018, Commercial unmanned flight – remotely piloted aircraft under 2kg, retrieved from https://www.casa.gov.au/standard-page/commercial-unmanned-flight-remotely-piloted-aircraft-under-2kg. *waiver available

Figure A2. DoD human factors analysis classification system (HFACS) version 7.0 coding flowchart adapted from the coding checklist on pp. 18-19 in The development and inter-rater reliability of the Department of Defense human factors analysis and classification, version 7.0, (AFRL-SA-WP-TR-2015-0009) by King, R. E., Strongin, T., Lawson, J., and Kuhlmann, E.W., 2015, retrieved from www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a623729.pdf

Appendix B

Tables

Table B1

HFACS v. 7.0 categories as analyzed in three UAS safety report databases

| Category | ASRS

(n = 30) |

ATSB

(n = 7) |

SAFECOM

(n = 24) |

HFACS Mean |

| Acts | ||||

| AE100 | 20.00% | 28.57% | 25.00% | 24.52% |

| AE200 | 86.67% | 85.71% | 83.33% (-0.002) | 85.24% |

| AV100 | 86.67% (0.07) | 14.29% | 0.00% | 33.65% |

| Preconditions | ||||

| PE100 | 20.00% | 0.00% | 12.50% | 10.83% |

| PE200 | 43.33% | 28.57% | 66.67% (0.01) | 46.19% |

| PC200 | 6.67% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 2.22% |

| PC500 | 13.33% | 42.86% (0.03) | 12.50% | 22.90% |

| PC100 | 26.67% | 57.14% (0.02) | 12.50% | 32.10% |

| PP100 | 3.33% | 14.29% (0.01) | 4.17% | 7.26% |

| Supervision | ||||

| SV100 | 6.67% (-0.13) | 0.00% | 0.00% | 2.22% |

| SP100 | 76.67% | 85.71% | 58.33% (-0.01) | 73.57% |

| SI100 | 20.00% | 14.29% | 0.00% | 11.43% |

| Organizational Influences | ||||

| OR100 | 26.67% | 0.00% (-0.02) | 20.83% | 15.83% |

| OP100 | 70.00% | 57.14% | 33.33% (-0.68) | 53.49% |

| OI100 | 40.00% (0.02) | 14.29% | 12.50% | 22.26% |

| OC100 | 53.33% (0.05) | 0.00% | 0.00% | 17.78% |

| HFACS Mean: | 37.50% | 27.68% | 21.35% |

Note. Statistical outliers (less than or greater than one SD) are in bold with variation in parentheses.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this assignment and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal