Building Information Modelling (BIM) Case Study

| ✓ Paper Type: Free Assignment | ✓ Study Level: University / Undergraduate |

| ✓ Wordcount: 5647 words | ✓ Published: 06 Jun 2019 |

SECTION1

Scenario 1

You receive an email from Mr Zhang’s head office with Mr Zhang copied in, saying that internal company procedures have recently changed, and they require the project details, as soon as possible (but definitely by the end of the first phase) to be presented as a cloud-based BIM system for full information sharing. The email mentions a recent Chinese research paper that states that “interoperability is the key to the success of cloud implementation” (Wong et al, “A Review of Cloud-Based BIM Technology in The Construction Sector”, Journal of Information Technology in Construction, ITcon Vol. 19 [2014], p281 ISSN 1874-4753).

The contractor and engineer have both been copied in agree that you are the best person to take on this task. The Project Manager points out that you have written “Attended several BIM workshops” on your website and, as the D&B contractor says, “the architect is always going on and on about how computers are the future”.

In a footnote, the original client email mentions that the Zed International Holdings is in talks with the China-British Business Council to be considered for government contract tender/bidding lists.

A few hours later, Mr Zhang’s legal advisor emails to say that Mr Zhang must be named as a system administrator with full editing authorization. Citing a Construction Manager report, she also adds in passing, that the client is not clear on what to do to comply with the BIM mandate.

Your response(s), please.

Undoubtedly, Building Information Modelling (BIM) offers many benefits such as organising and sharing building information systematically and easily between the various members of the team throughout a project lifecycle. In addition, promote greater transparency and collaboration between suppliers and thereby reduce waste (procurement, process and material) through all levels of the supply chain.

However, adopting BIM is a major change which involves the all team learning a new software and a new way of delivering projects. In addition, BIM places new demands on our infrastructure and hardware: exchanging of data internally and externally requires a reliable internet connection and a strong internal network and server as well as robust hardware on office computers. Thus, BIM is not about only installing a software but requires change and a vigorous change management. Understanding this at this stage will help avoid many of the difficulties associated with adopting BIM. Misunderstanding this will highly likely leave our firm in trouble (GOV.UK, 2012).

The original client email mentions that the Zed International Holdings is in talks with the China-British Business Council to be considered for government contract tender/bidding lists. As anyone involved with a government project will be contractually obligated to use BIM, adopting BIM will be unavoidable. However, we must plan the adoption process very carefully. One way of applying this is to implement the new model gradually. We can start using it to produce design documents, which refers to ‘Level 1 BIM’. In this model, BIM will only be used internally and not be shared with the Head Office. In this case, we will communicate with the Head Office using traditional drawings sets. This will give us enough time to train the staff and the model be adopted to avoid possible mistakes during the application of the training. We can only achieve ‘Level2 BIM’ or ‘Collaborative BIM’ once the whole team is more comfortable (AUGI, 2014).

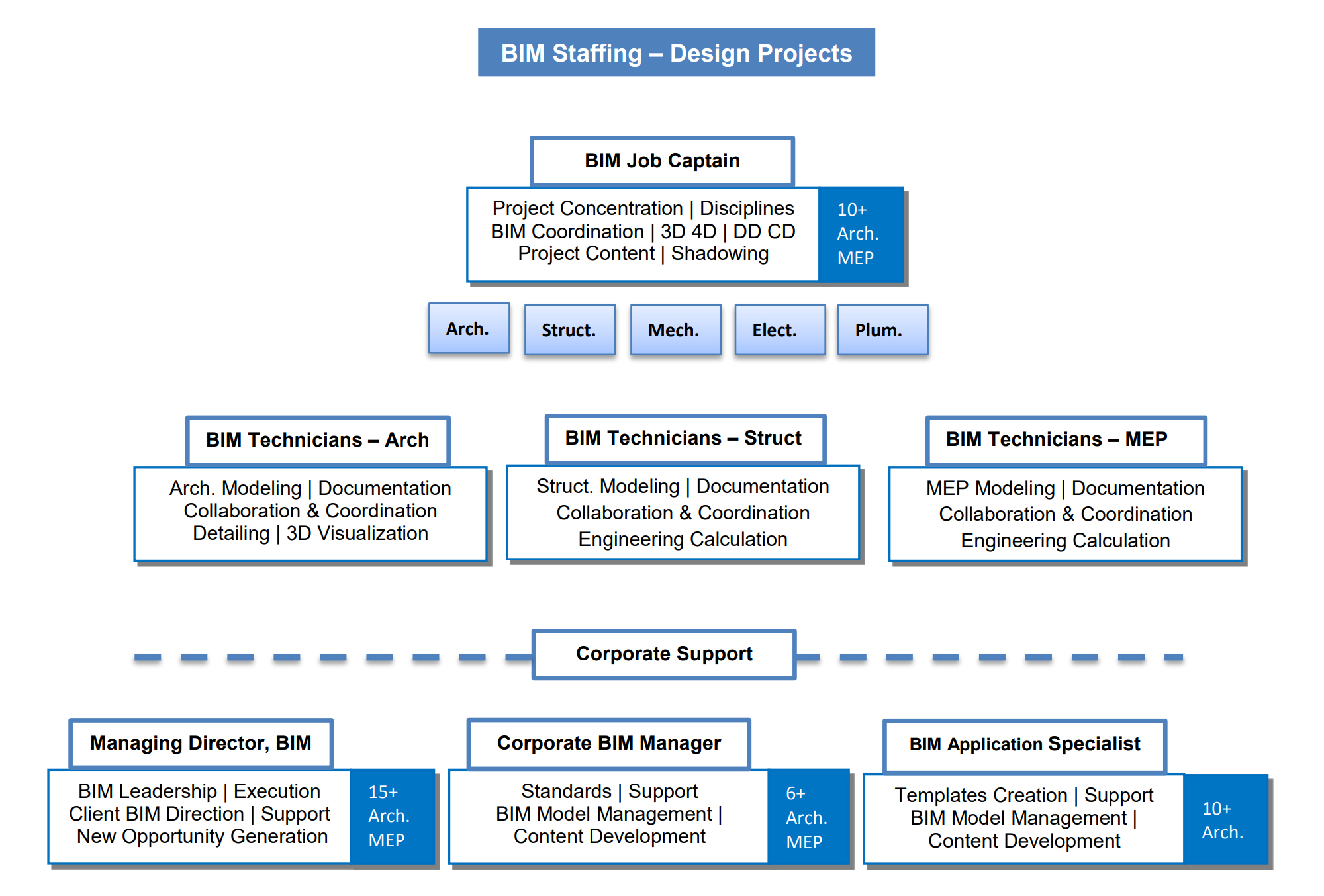

If we manage the overall process appropriately, changing to Collaborative BIM will be easier to initiate. At this stage, having dedicated staff to guide the transition as well as the resources to absorb potential disruptions will be beneficial to our team (Bew, 2015). Thus, for a smooth adaptation, it is important to us to consider employing a BIM manager/ System Administrator, which must be a technical professional with experience in delivering BIM projects.

System Administrator is a serious title that needs to be taken very seriously, as it determines the success of the BIM project. Also, it is a full-time job which requires the knowledge of architectural design and construction practices, methods for organizing design and construction documents, project manuals, building codes and bidding documentation, among many others. Thus, this role is not suitable for Mr Zhang.

I will write to Head Office to kindly explain the responsibilities of System Administrator and answer their question about BIM mandate.

Dear Mrs X,

Building Information Modelling (BIM) can help our firm operate more productively through saving costs and time, produce higher-quality work. However, adopting BIM will require training of the team, and design infrastructure of the office to support expected workload.

Thus, If the Head Office requires our office to implement BIM, it will be more appropriate to use BIM just internally in the beginning. Although this is a basic application of BIM, it will be more appropriate to start with. As soon as we achieve desired results and the whole team is more comfortable, we can move on to Collaborative BIM and consider appointing a System Administrator, which will manage the daily BIM Management duties.

Regarding your question about BIM mandate, since April 2016 anyone involved with a government project in the UK is contractually obligated to use BIM. BIM mandate is a part of the Government Construction Strategy (GOV.UK, 2011), which is a policy paper issued by the UK Government. This policy only applies to publicly procured projects. Nevertheless, with the right infrastructure and training in place, we will be prepared for government contract tender/bidding lists.

I hope that the above answers your questions satisfactorily. Should you have any further questions, please do not hesitate to contact me.

Yours sincerely,

A.C.

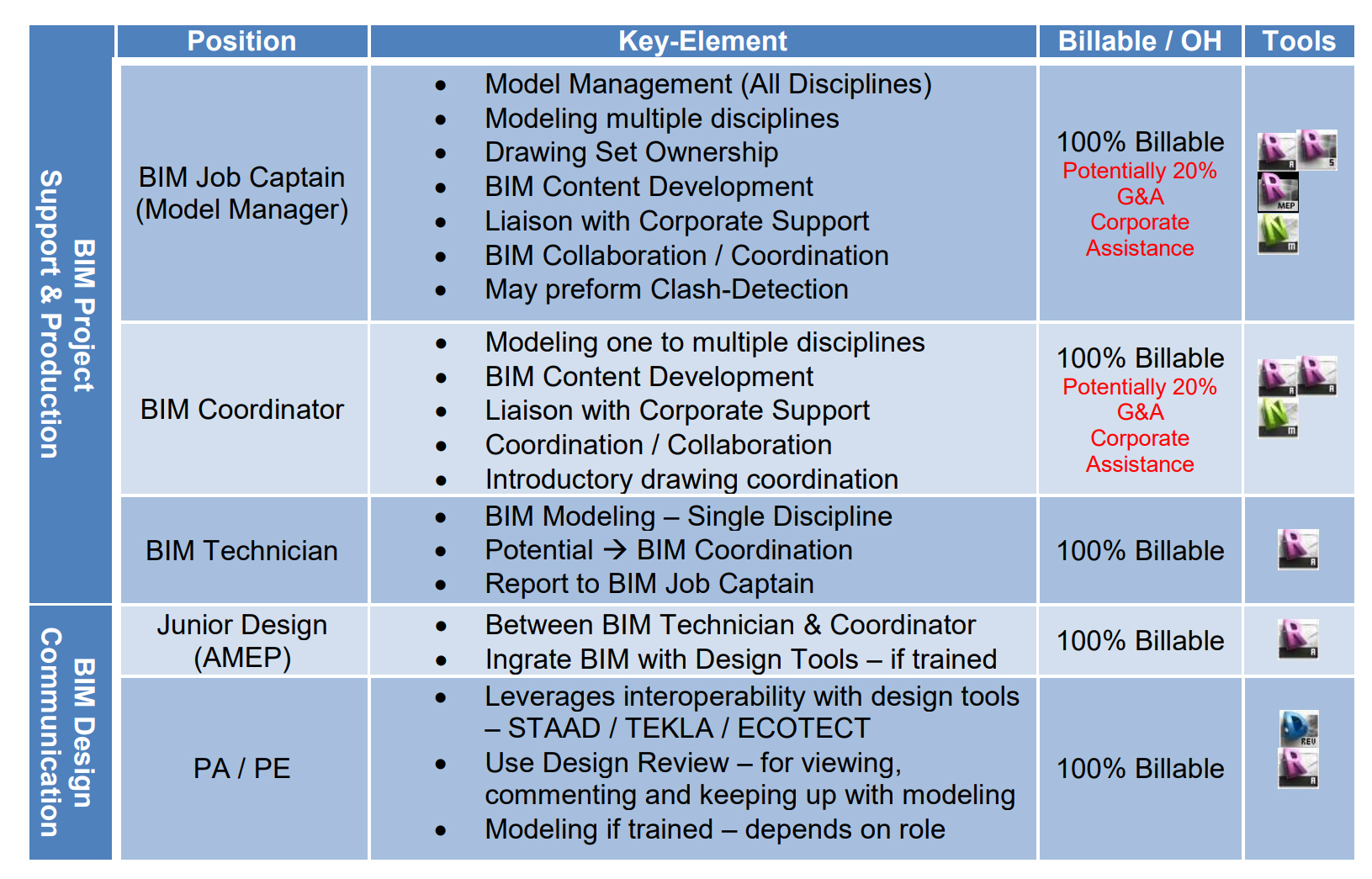

PS: I have attached two diagrams showing BIM Organisational Structure.

Attachments:

BIM Staffing- Design Projects, (Autodesk and Joseph, 2011)

Design BIM Staff, (Autodesk and Joseph, 2011)

Scenario 2

You receive a text at 2am in the morning.

“The stable block is on fire. Just discovered. Fire brigade called but beyond salvation. Good job insured. Look on the bright side. Opportunity to rebuild new proposal with insurance funds.”

Your thoughts? Actions?

Because the whole stable block is destroyed by the fire, the claim process may not be as easy as Mr Davies assumes. The fire has affected not only the construction works but also the existing stable block. Depending on the insurance type chosen, this may create complications during the claim process (RICS, 2018).

If the Contractor insured the building works and Mr Davies insured the existing stable block, both Mr Davies and the contractor will need to contact their insurers immediately. Subsequently, each insurer will appoint their own loss adjusters, who will argue over which policy the damage falls under. In this case, the risks associated with the construction project on the building site will be covered by a policy called Contractor’s All Risks Insurance (CAR) or Contract Works Insurance (CWI), which is obtained by the contractor (Chappell and Willis, 2010). The CWI is commonly issued under the joint names of a contractor and the client and normally covers all risks of physical loss or damage such as a fire, flood, storm, theft, or vandalism thus, can protect against the cost of unforeseen loss or damage to building works and public liability etc.

CWI provides cover for work that is in progress at the building site as well as for defects found during final testing and for issues during handover (Reed, 2018). This means that if the works and the building are insured separately, the Contract Works Insurance will only cover the cost of redoing the work that has been damaged by the fire. Also, to recover the total cost of the building works, CWI bought by the contractor will need to be in a cover level that matches the total cost of his largest project. Because CWI will cover the construction works not the existing building on the site, stable block should be covered by the client’s home insurance or the building works and the stable block is insured under one policy. In this case, the insurers for the stable block will undoubtedly exclude all losses arising out of the activities of the contractors and restrict Mr Davies’ insurance to very limited cover.

On the other hand, if Mr Davies and the contractor transferred the existing structure cover onto a works policy and insured it in conjunction with the works, they will meet the requirements under a JCT Contract thus receive much wider cover from one insurer.

I will recommend Mr Davies to check his insurance documents carefully to see what is covered and what is not. There may be certain conditions that he needs to meet to be covered including keeping the fire doors closed or having fire extinguishing appliances serviced regularly. If he doesn’t meet these conditions, the insurance company may reject the claim.

Scenario 3

After considering the situation with the neighbours’ complaints (see previous Assignment), the Chair of the local authority Planning Committee rings you up. He explains that there is a growing list of issues of concern (neighbours are now worried about The Coppers’ interest in removing trees, altering the character of the street, conducting business activities where criminals maybe coming to a barrister’s house, the possible reduction in the value of their properties, etc). The local authority notes that the project has Planning Permission, but these complaints are getting out of hand and the council is spending an inordinate amount of time dealing with complaints. They say that they are calling a public meeting in the Town Hall and suggest that you attend. They recommend that you draft a guest list, agenda (including other preparatory issues, precedent studies, and attachments/drawings, etc. that you think might be useful) and a 10-minute introduction.

Over to you…

We submitted the planning application following necessary procedures, relevant legislation, and guidance. Before the Planning Permission is granted, the Local Planning Authority has published the planning application and given enough time to the neighbours to complain. During this period, Mr and Mrs Copper’s neighbours probably wrote to the Local Authority give their reasons why they think the application should not be approved. Following this, the Planning Department assessed the planning application against the local development framework (LDF), The London Plan as well as any other relevant development plans and policies and; considered ‘material considerations’.

Under UK law, if a Local Authority has received several planning complaints regarding the works after the Planning Permission is granted, it is required to investigate if there has been a breach of planning control. This also includes some of the complaints raised by Mr and Mrs Copper’s neighbours such as construction and/or changing the use of bulding; and removal of protected trees without Planning Permission etc (BCC, 2018). As a result of this investigation if the Planning Department finds out that building work has been carried out without Planning Permission or it is being used for an unauthorised purpose it can issue an enforcement notice (PlanningHelpline, 2018). However, as the Local Authority states in their letter the project has Planning Permission and the building works continues under granted laws. Therefore, they cannot issue an enforcement notice to Mr and Mrs Davies.

The council states that it is spending an inordinate amount of time dealing with complaints. However, it is Local Authority’s responsibility to reply to such complaints from the public, considering that the works are going lawfully. Thus, even if they call a public meeting in the Town Hall, they cannot force me or Mr and Mrs Copper to attend this meeting. Besides, drafting a guest list and agenda (including other preparatory issues, precedent studies, and attachments/drawings, etc.) will cost my clients a considerable amount of money and time. In addition, it won’t be productive, as most of the complaints are based on speculation. Thus, I will write to the Planning Department to kindly let them know that we won’t be able to attend this meeting.

On the other hand, although the law doesn’t allow anyone to appeal against the Council’s decision to government bodies, if the neighbours believe that the Council’s decision of granting Planning Permission to Mr and Mrs Copper’s project was wrong, they can contact a public advocate known as an Ombudsman, which is an official who is charged with representing the interests of the public by investigating and addressing complaints of maladministration or a violation of rights.

SECTION 2

1. In 100 words each provide a synopsis of the following case law and identify the salient points of the case. Additionally (maybe 200-400 words in each case), include: the judgement; its application, relevance, and significance, and; your thoughts on the matter.

• MacInnes v Gross [2017]

MacInnes V Gross [2017] EWHC 127 (QB) is a case on contractual arrangements, contract formation.

Mr MacInnes (the Claimant) was an investment banker who had several discussions with Mr Gross (the Defender) over a number of years to grow Mr Gross’ business -RunningBall. Eventually, in March 2011, following various exchanges between them, Mr MacInnes and Mr Gross talked about the potential sale of Mr Gross’ business over dinner at a restaurant. Mr MacInnes later alleged that he made an oral contract with Mr Gross at that dinner to provide services to him. This included maximising Mr Gross’ return on the sale of the RunningBall business. In exchange, he would “receive remuneration calculated by reference to a formula which gave him 15% of the difference between the ‘strike’ (or target) price of RunningBall and the actual sale price”(BAILII, 2017). Mr MacInnes brought a €13.5m claim against Mr Gross for breach of contract but Mr Gross denied this stating that there was any binding contract between himself and the claimant. The High Court rejected the claim for the main reason that “the parties had not manifested an intention to create legal relations but also the absence of certainty in relation to other fundamental terms”(RCP, 2017).

The decision highlights the dangers of informality in contractual dealings (and documenting them), particularly when the subject matter is high value. Mr MacInnes’ belief was that it was agreed that he would personally provide services to Mr Gross and/or Mr MacInnes company for which he would be remunerated. Mr MacInnes had taken a relaxed approach believing that he had the security of enforceable rights when none in fact existed (Walker and Morris, 2017).

• Compare and contrast the case of Anns v Merton and Murphy v Brentwood

Anns v Merton London Borough Council [1977] UKHL 4, [1978] AC 728 is a case on duty of care in English law. This case was later overruled by Murphy v Brentwood District Council [1991] UKHL 2, [1991] 1 AC 398.

In the case of Anns v Merton 1977, Anns (the Claimants) were tenants in a flat in Merton. The flats suffered from structural defects due to inadequate foundations which were 2ft 6in deep instead of 3ft deep as required. Merton London Borough Council (the Defendants) was responsible for inspecting the foundations during the construction of the flats. The House of Lords held that the defendant did owe a duty of care to ensure the foundations were of the correct depth. It established a two-stage test for determining the existence of a duty of care in the tort of negligence called the Anns test. The first stage being whether there is a sufficient relationship of proximity between the wrongdoer and the person who has suffered; in which case an on the facts duty of care arises. Secondly if the first question is answered yes, whether there are any considerations which reduce the duty owed.

In the case of Murphy v Brentwood, the Local Authority (the Defendant) failed to inspect the foundations of a building adequately. When the building became dangerously unstable, Mr Murphy (the Claimant) could not afford the repairs and had to sell the house at a loss which he sought to recover from Brentwood District Council. However, his claim was unsuccessful because the loss was identified as a pure economic loss. This case overruled the decision Anns v Merton London Borough Council with respect to duty of care in English law.

In the cases of Anns v Merton and Murphy v Brentwood, the grounds for action was for the court to consider if the local authorities were under any duty of care towards owners or tenants of houses regarding inspection during the building process. Yet, different approaches have been taken in deciding the issue of duty of care and negligence. In Anns v Merton case, the judge proposed a new two stage test for the duty of care. Rejecting the two-stage test in Anns v Merton, Murphy v Brentwood allowed later courts to develop new categories of negligence by using previous cases.

• Signature Realty v Fortis Developments [2017]

Signature Realty Ltd v Fortis Developments Ltd [2016] EWHC 3583 (Ch) is a case on copyright infringement.

Signature Realty Ltd (the Claimant) is a property development company which had taken an interest in purchasing a site with two office buildings in Sheffield city centre. Signature commissioned C&W architects to prepare design drawings to apply for planning permission to develop the offices into residential apartments. However, the site was sold to Fortis Development (First Defendant) by the landowner (Second Defendant). Following the purchase of the site, defendants together developed the buildings into student accommodation using Signature Reality’s design and construction drawings that they downloaded from Sheffield City Council’s website without any permission/licence. The drawings were also used for marketing the properties, tendering and estimating purposes.

After getting the copyright from C&W, Signature Realty Ltd sued Fortis for infringement of its copyright in the design drawings. Subsequently, the Court found Fortis guilty of copyright infringement and ordered Fortis to compensate Signature for unauthorised use of its copyright. The Court held that Fortis had infringed Signature’s copyright in the design drawings by altering and/or using the copies of their drawings for design, construction, tendering and marketing purposes.

However, Signature Realty Ltd could only sue Fortis for copyright infringement after it purchased the copyright from C&W. Fortis should have had the permission of C&W -the owner of the intellectual property rights in the design drawings before they used them. The fact that Signature Realty Ltd made design drawings available to download and view on Sheffield City Council’s website did not mean that they were free for anyone to use as they wish.

• Hedley Byrne v Heller [1964]

Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v Heller & Partners Ltd [1964] AC 465 is an English tort law case on pure economic loss resulting from a negligent misstatement.

Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd (the Claimant) was an Advertising Agency which had made a large order for a client, Easipower Ltd. Thus, Hedley Byrne sought reassurance that they could provide credit to Easipower and contacted Easipower’s bank Heller & Partners (the Defender). The bank reassured the financial stability of their client stating that they considered Easipower Ltd “good for its ordinary business engagements” and “trustworthy, in the way of business, to the extent of £100,000 per annum advertising contract”. However, the letter was headed a disclaimer that the letter was ‘without responsibility on the part of the bank or its officials’. In reliance on the reference from the Heller & Partners, Hedley Byrne placed orders for advertising for Easipower Ltd. Soon after giving credit, Easipower Ltd. went into liquidation. As a result, Hedley Byrne lost a considerable amount on contracts thus sued Heller & Partners for negligence, claiming that the information was given negligently and was misleading. Heller & Partners argued there was no duty of care owed regarding the statements, and, in any case, liability was excluded. The court found that the relationship between the parties was “sufficiently proximate” as to create a duty of care. However, on the facts, the disclaimer was found to be sufficient to discharge any duty created by Heller’s actions.

If the advice was given without a disclaimer, the advice-giver assumes at least some sort of responsibility. However, here was a disclaimer, and therefore there is no liability. This decision established that the duty of care doesn’t have to be written into the contract to exist, it automatically arises where individuals perform acts that could foreseeably harm others. Thus, if a ‘special relationship’ exists between individuals, pure economic loss resulting from negligent misstatement can be recovered.

The decision provided the genesis for the growth of professional liability principles by recognising that a duty of care may arise in circumstances where a party relies on the skill or expertise of another party.

• Carillion Construction Ltd v Woods Bagot Europe Ltd and others [2016] EWHC 905 (TCC)

Carillion Construction Ltd v Woods Bagot Europe Ltd and others [2016] EWHC 905 (TCC) is a case on contiguous extensions of time and extinguishing liability for liquidated damages.

Carillion Construction Limited (the Claimant) was a contractor which was engaged by Rolls Development UK Ltd in June 2007 to build the High Court’s Rolls Building in London using the JCT Standard Form of Building Contract with Contractor’s Design, 1998 edition (incorporating Amendments 1:1999, 2:2001 and 4:2002), together with bespoke amendments. This provided for sectional completion and had the usual provisions relating to liquidated damages and extensions of time upon the occurrence of a “Relevant Event”. The works were delayed in November 2010. Carillion and Rolls subsequently entered into a supplemental agreement agreeing that Carillion had no claims for an extension of time and agreeing a new contract sum which included the Carillion’s liability for liquidated damages. Further delays occurred again and both parties entered into a second supplemental agreement in July 2011. Carillion engaged sub-contractors EMCOR Engineering Services Ltd and AECOM Ltd for the provision of mechanical and electrical services.

The TCC considered preliminary issues relating to the damages for delay to the construction of the Rolls Building, where the TCC itself sits. The Contract between the claimant contractor and defendant sub-contractor was in the standard JCT Sub-Contract DOM/2 form which allowed an extension of time for the works beyond the completion date “or any revised such period” in the event of delay. The clamant sought costs associated with delay as well as to pass down the liquidated damages the developer had deducted under the main contract. The sub-contractor claimed it was entitled to an extension of time, and also disputed the contractor’s liability to the developer. The preliminary issue concerned whether, on the assumption the sub-contractor was entitled to an extension of time, the revised periods for completion of the sub-contract works were to be added contiguously to the end of the revised period for completion, or whether they should be fixed so as to reflect the period for which Emcor was in fact delayed, which could therefore be discontinuous with the revised completion date. The Judge held that the natural meaning of the clause was that the additional period was to be contiguous to the pre-existing period. There would not be a fresh and potentially discontinuous period for completion added onto a future date when the variation arose

Carillion commenced court proceedings against EMCOR and AECOM for (among other things) the delay caused by each sub-contractor in which it claimed its own costs as well as those it was liable for under the Contract.

Carillion claimed amongst other things damages caused by delay to the carrying out and completion of both EMCOR and AECOM’s sub-contract works. This delay in turn led to liquidated damages being levied against Carillion by Rolls.

EMCOR argued that it was entitled to an extension of time, with both EMCOR and AECOM affirming that neither should be held liable for liquidated and ascertained damages because Carillion had no liability to Rolls for such damages, and/or had not paid such sums to Rolls and/or that such sums had not been deducted from sums otherwise payable by Rolls to Carillion

A dispute arose between Carillion and EMCOR in relation to damages that Carillion say were caused by the sub-contractor’s delay which in turn led to liquidated damages being levied against Carillion by Rolls.

The Court found that both parties “agreed by reference to a particular date, that there would be no extension of time granted to Carillion” in relation to any incidents of delay leading up to the date of the further supplemental agreement.

Miss Recorder Nerys Jefford QC, sitting as a judge of the Technology and Construction Court (TCC), held that and extension of time should be added contiguously and that the contractor’s liability to the employer was not extinguished.

This case confirms that extensions of time caused by delay will run contiguously unless expressly provided for in the contract.

Also, this case illustrates that liquidated damages already incurred will not be extinguished by virtue of parties agreeing to extend the date for practical completion. As stated by Ms Nerys Jefford QC “the fixing of new Dates for Completion is a means of drawing a line under previous claims but not of granting extensions of time”. If parties want the benefit of a new date for completion extinguishing a claim for previously accumulated liquidated damages, the contract or contract variation should be drafted to reflect this.

Although the court focused on the natural meaning of the EMCOR contract the court did acknowledge contractual agreements could operative to absolve the sub-contractor of some liability in certain situations. This allows employers to amend contract provision to furnish for those situations. Contractors will be relieved by the court’s finding that the further supplemental agreement did not extinguish the contractor’s liability for liquid dated damages. The ability to compromise claims under a main contract can be key to developing large projects, so any judicial authority that made such compromise more difficult would be challenging.

2. What is a Framework Agreement – why are they used and what are their benefits and drawbacks?

A framework agreement is an agreement between businesses or organisations that sets out the terms concerning price, quality, and quantity under which individual contracts or call-offs can be made throughout the period of the agreement, which is normally a maximum of 4 years. Framework agreements can take one of two forms: 1) Single supplier framework, 2) Multi-supplier framework. Although a framework agreement is not generally a contract, the procurement exercise to establish a framework agreement is subject to the public procurement rules.

The framework agreement is beneficial for the companies that are continuously contracting construction work, as they only have to go through the tender procedure once. This reduce procurement timescales, tendering costs as well as learning curves and other risks, allowing a purchaser more flexibility around the goods or services. The reduction to tendering costs will also apply to suppliers, as going through the tender procedure is costly and time-consuming for suppliers too.

On the other hand, framework agreements are relatively unresponsive to change, as sometimes their ‘one size fits all’ approach fail to respond the needs of the new suppliers and/or new solutions. This also make it difficult for authorities to satisfy their own procurement objectives. The main disadvantage of those agreements is that they do not guarantee that suppliers will get any business from them, as they do not place any obligation on the purchasers to buy goods, works or services.

3. Read thoroughly, information pertaining to the government’s New models of construction procurement. Explain the meaning of:

• Two Stage Open Book,

• Cost Led Procurement, and

• Integrated Project Insurance

Provide a brief synopsis of each, a critique/ assessment of their merits/demerits and provide a critical assessment of their potential applications.

The Government case studies has shown that “construction industry poses a distinctive set of procurement, supply and project management challenges, in both the private and public sectors” (CabinetOffice, 2014). Thus, in February 2014, as a part of the Government Construction Strategy, the Government introduced three new construction procurement models that are aimed to reduce the costs during the construction process for both government and industry: Two Stage Open Book; Cost Led Procurement (CLP); and Integrated Project Insurance (IPI). Aimed to provide cost certainty in the beginning of a construction project, the models include principles of early supplier engagement, transparency of cost, integrated team working and collaborative working (CabinetOffice, 2014).

- Two Stage Open Book (2SOB)

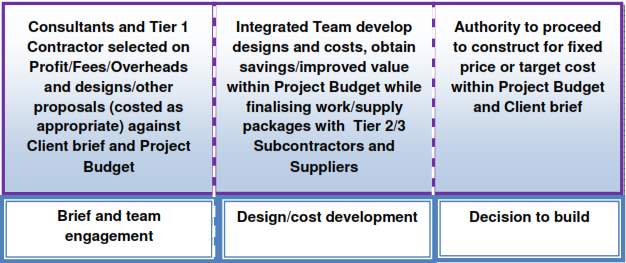

This model is structured similar to two stage tendering. At stage 1, a client invites prospective integrated teams to bid for a project. Following the bidding competition, a team is appointed on grounds of capability, experience, efficiency etc. The appointed team work up a proposal with the client on the basis of an open book cost. At Stage 2, the main contract for works is awarded (KCL, 2014).

2SOB is different from Cost Led Procurement in the way that it reduces industry bidding costs, enables faster mobilisation, and provides the opportunity for clients to work earlier with a single integrated team.

The key feature of this model is the early involvement of the project team to curtail risks, develop the design and agree a fixed contract price before starting on site (GOV.UK, 2014).

Fig1. The flow chart summarising the two-stage, open-book process (KCL, 2014).

Fig1. The flow chart summarising the two-stage, open-book process (KCL, 2014).

- Cost Led Procurement (CLP)

This model is a two-stage process that is mainly used with framework agreements. At stage 1, two teams are selected to move to the Stage 2 to refine their proposals. The team is selected based on their ability to bring the project costs in below its cost benchmark. If none of two selected teams are able to deliver the work within the affordable budget, the project is then offered to suppliers outside the framework. If the scheme price still cannot be matched or bettered, the projects does not proceed. Under these circumstances, client may have to review and update the requirements to proceed the project.

The disadvantage of the Cost Led Procurement is that the client is given responsibilities to select a realistically challenging price. On the other hand, the advantage of CLP is that it offers the opportunity for further reduction of costs in subsequent projects, working collaboratively with the supply chain. This is beneficial for the clients continuously commissioning construction work, as using framework agreements helps reduce procurement timescales, learning curves and other risks. In this respect, “this model is suitable mainly for projects where costs cannot be exceeded and are repeatable, for example, the construction of schools and roads” (GOV.UK, 2014).

- Integrated Project Insurance (IPI)

In this model, members of an integrated project team are appointed through a competition. The chosen team is selected based on elements assessing competence, capability, experience, proven track record, efficiency, fee declaration etc. Consequently, the team forms an ‘alliance board’ with the client to prepare a proposal considering the required outcome and cost benchmark. Different to the existing procurement models, the whole project is underwritten by a single (third party assured) insurance policy covering risks associated with delivery of the project, such as cost overruns (CabinetOffice, 2014).

The advantage of The Integrated Project Insurance model is that ‘Alliance Board’ formed allows clients to create an integrated project team. This help eliminate any conflicts or battles amongst the team, limiting the risks to each member. In addition, the ‘Integrated Project Insurance’ package limits the risk to the individual members of the team, fosters joint ownership of the project, and thereby reduces the likelihood of overrunning in terms of cost and time (GOV.UK, 2014).

However, in this model, in order to secure the insurance, the team will have to prepare a credible proposal, validated by the independent expert assurer to ensure that the commercial tension is maintained, and that the insurer is comfortable that it can be delivered.

Bibliography

AUGI. 2014. How small firms should prepare for the BIM 2016 mandate [Online]. Autodesk User Group International. Available: https://www.augi.com/articles/detail/how-small-firms-should-prepare-for-the-bim-2016-mandate [Accessed 1 March 2018].

AUTODESK & JOSEPH, J. 2011. BIM Titles and Job Descriptions: How Do They Fit in

Your Organizational Structure? [Online]. Autodesk University. Available: http://aucache.autodesk.com/au2011/sessions/4436/class_handouts/v1_DL4436_Joseph_BIM_Titles_Job_Descriptions_JJ.pdf [Accessed 18 March 2018].

BAILII. 2017. England and Wales High Court (Queen’s Bench Division) Decisions: MacInnes v Gross [2017] EWHC 46 (QB) (27 January 2017) [Online]. BAILII. Available: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/QB/2017/46.html [Accessed 05 March 2018].

BCC. 2018. Make a planning complaint [Online]. Birmingham City Council. Available: https://www.birmingham.gov.uk/info/20160/planning_applications/23/planning_enforcement [Accessed 09 March 2018].

BEW, M. 2015. Life beyond BIM Level 2 [Online]. the Association for Consultancy and Engineering. Available: http://www.infrastructure-intelligence.com/article/oct-2015/life-beyond-bim-level-2 [Accessed 28 February 2018].

CABINETOFFICE. 2014. New Models of Construction Procurement [Online]. Cabinet Office. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/325011/New_Models_of_Construction_Procurement_-_Introduction_to_the_Guidance_-_2_July_2014.pdf [Accessed 28 February 2018].

CHAPPELL, D. & WILLIS, A. 2010. The Architect in Practice, Chichester, West Sussex, U.K. ; Ames, Iowa, Wiley-Blackwell.

GOV.UK. 2011. Government Construction Strategy [Online]. GOV.UK. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/government-construction-strategy [Accessed 18 March 2018].

GOV.UK. 2012. Industrial strategy: government and industry in partnership [Online]. GOV.UK. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/34710/12-1327-building-information-modelling.pdf [Accessed 13 March 2018].

GOV.UK. 2014. New models of construction procurement [Online]. GOV.UK. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/new-models-of-construction-procurement [Accessed 27 February 2018].

KCL. 2014. PROJECT PROCUREMENT AND DELIVERY GUIDANCE: Using Two Stage Open Book and Supply Chain Collaboration [Online]. Cabinet Office, King’s Collage London. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/325014/Two_Stage_Open_Book_Guidance.pdf [Accessed 27 February 2018].

PLANNINGHELPLINE. 2018. Planning Enforcement Notice [Online]. Planning Helpline. Available: http://planninghelpline.com/planning-enforcement/planning-enforcement-notice/ [Accessed 03 March 2018].

RCP. 2017. Back to first principles: contractual intention [Online]. RCP. Available: https://www.rpc.co.uk/perspectives/commercial-disputes/back-to-first-principles-contractual-intention [Accessed 12 March 2018].

REED, P. 2018. Contractors’ All Risks Insurance (CAR) [Online]. Thomson Reuters Practical Law. Available: https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/4-618-5203?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)&firstPage=true&bhcp=1 [Accessed 11 February 2018].

RICS. 2018. Construction all risks (CAR) insurance [Online]. The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS). Available: http://www.rics.org/uk/shop/BCIS-Online-Rates-Database—All—Premium—1-User-19440.aspx [Accessed 16 February 2018].

WALKER & MORRIS. 2017. Commercial contract formation: Don’t forget first principles [Online]. RCP. Available: https://www.walkermorris.co.uk/publications/disputes-matter-spring-2017/commercial-contract-formation-dont-forget-first-principles/ [Accessed 03 March 2018].

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this assignment and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal